The Science Of Scientific Writing Set G The Introduction The Pivot Point of the Paper Challenges to Coherence Exercise 1 Hand in Glove Exercise 2 Final Page .

OVERVIEW: The way to well-written science

PART I: Paragraphs and Sentences

SET A: Paragraphs: The Maps Behind Them

SET B: Paragraphs: Using Maps to Meet Readers' Expectations

SET C: Paragraphs with Something Extra: Points and Tails

SET D: The Generic Section: Expectations and Maps as Blueprints

SET E: Scientific Sections: The Methods and Results

SET F: Scientific Sections: The Discussion

SET G : Scientific Sections: The Introduction

SET H : Sentences

SET I : The Paper as a Whole

PART II: The Paper and its Sections

SET 1: Argument Parts

SET 2: Indicator Words

SET 4: Locating Arguments in Prose

SET 5: Rationale's Essay Planner

SET 6: Evidence in Arguments: Basis Boxes

Synthesis 1: Position-Early Paragraphs

Synthesis 2: Position-Final Paragraphs

Synthesis 3: Writing a Discussion I

Synthesis 4: Writing a Discussion II

Set G: The Introduction

The Introduction does not present as huge a writing task as does the Discussion, but this is only because of its brevity: "per inch" of text the Introduction is typically considered more challenging to write. This is due to the difficult nature of an "introduction" in any genre of communication whether it be a seminar, a book, or a movie. You are "talking" to your audience for the first time, and in a logical, stepwise manner you must quickly build a bridge of common understanding. We all know first impressions count, and many readers will actually be looking to your Introduction as a broad "litmus test" of your paper's value: it will not only state the basics (i.e. the research question, objectives) but it also provides strong clues as to whether the information is likely to be extractable without excess reading effort.

Luckily, despite its challenges, the Introduction is probably the best understood of the sections of a paper. Research into the structure of Introductions tells us what readers expect, and from it, and our previous understanding of generic section structure, emerges a simple template for you to work from. But working blindly from a template is of course not a good thing: we need to know why and how such a predictable pattern structures could have evolved.

Background to Introductions

The purpose of the Introduction is to convince the reader that there exists at least one unresolved question or problem of scientific interest, that can be profitably addressed by the application of some currently available methodology. As such the Introduction is an argument with three claims, two of which are sub-claims:

* There is a problem, X

* The problem X is of scientific interest

* The problem X is tractable

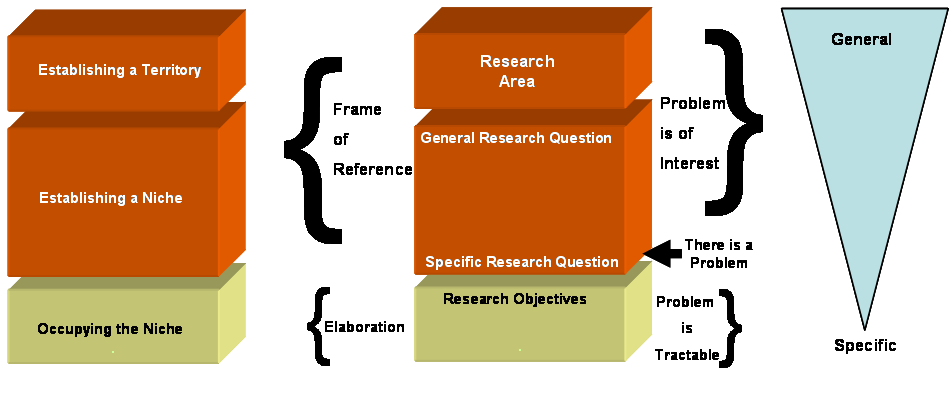

While the Introduction is argumentative, it rarely feels like one, because the claims above are usually argued with a certain degree of implicitness. In fact, analysis of the the Introductions of research articles shows that they have evolved a very idiosyncratic three-"move" structure (described in the book Genre Analysis, by John Swales). Swales uses terminology ("territory" and "niche") from animal ecology to describe the three moves. (A niche is a restricted aspect of a territory: for example, a leopard and a tiger might occupy the same territory, but their niches will not overlap entirely because they each prefer different-sized prey).

The Three Moves of Research Paper's Introduction (according to Swales)

1. Establishing a territory

2. Establishing a niche

3. Occupying the niche

With respect to (1) the two-part generic section structure introduced in Set D, (2) the nested nature of research questions explained in Set F, and the (3) three argument claims noted above, the first two diagrams below show how these all align with Swales' three moves:

The third of the diagrams, the inverted triangle, is meant to emphasise that as we progress through the different moves (or research questions), we are gradually narrowing our focus. We must go in this direction (rather than specific to general) because the more general information is needed to provide a context for the reader to understand the specific research question. It also introduces terminology used in the field, allowing the author to state the specific research question in a succinct form

Note that in the central diagram, each of the three coloured blocks is meant to be a single paragraph. I believe most Introductions do not require any more than three paragraphs. Here, for example, are links to PDFs of two of my own papers that use the three-paragraph format (Paper 1, Paper 2) and a third paper with a four-paragraph Introduction (Paper 3, in which the second move is expanded into two paragraphs). Note also that the second paragraph has a classic Point-final structure (General question-Specific Question), described on this page in Set D.

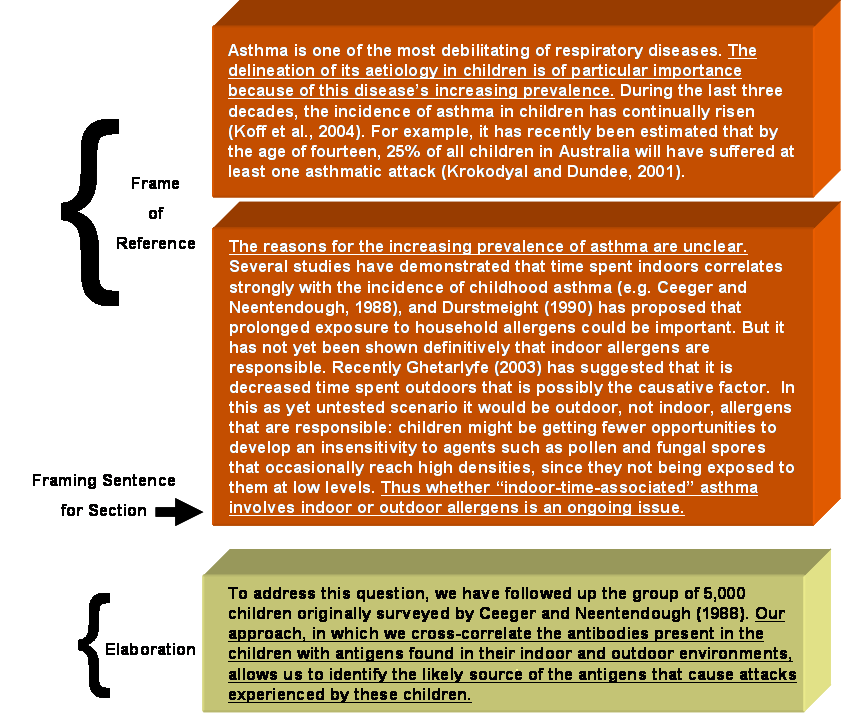

The diagram below revisits the structure of the Introduction to our fictional paper about childhood asthma. Each paragraph corresponds to one of the moves of the Swales system. The sentences that best express the four nested questions of the paper are underlined:

The three tables below show sets of questions for two other possible papers. Note that in the third example, the paper immediately starts with a more specific question than in the otherwise identical second example. The degree of specificity you choose for the first question/issue will depend upon your target audience: the more specialised they are in the area of research, the more specific your initial question can be. Having said that - it usually pays to underestimate your audience!

Example |

How the question relates to the question or issue above | Scientific Significance | |

| Research Area | What is the origin of life? |

A general field of work in which there are many questions, some tractable, some intractable |

Very high |

General Research Question |

Does life arise by spontaneous generation? | The question is general and often intractable, and any answers to it indirectly address the Research Area. | High |

| Specific Research Question | Can spontaneous generation occur with just two components: any organic matter, and pure air? | The question is specific and tractable, and its answer indirectly addresses the General Research Question (above). | "Sufficient" |

| Research Objective | Does boiled meat broth in a flask whose contents are in contact with room air, but not with the dust in the air, become cloudy? | The question is very specific and tractable, and its answer directly addresses the Specific Research Question (above). | "Insufficient" |

.

Example |

How the question relates to the question or issue above | Scientific Significance | |

| Research Area | Global warming |

A general field of work in which there are many questions, some tractable, some intractable |

Very High |

General Research Question |

What causes global warming? | The question is general and often intractable, and any answers to it indirectly address the Research Area. | High |

| Specific Research Question | Which atmospheric gas, carbon dioxide or methane, absorbs the most infrared radiation? | The question is specific and tractable, and its answer indirectly addresses the General Research Question (above). | "Sufficient" |

| Research Objective | At what frequency do the C-O and C-H bonds of carbon dioxide and methane, respectively, vibrate? | The question is very specific and tractable, and its answer directly addresses the Specific Research Question (above). | "Insufficient" |

.

Example |

How the question relates to the question or issue above | Scientific Significance | |

| Research Area | What causes global warming? |

A general field of work in which there are many questions, some tractable, some intractable |

Very High |

General Research Question |

Which atmospheric gases are more likely to cause global warming? | The question is general and often intractable, and any answers to it indirectly address the Research Area. | High |

| Specific Research Question | Which atmospheric gas, carbon dioxide or methane, absorbs, volume-per-volume, the most infrared radiation? | The question is specific and tractable, and its answer indirectly addresses the General Research Question (above). | "Sufficient" |

| Research Objective | At what frequency do the C-O and C-H bonds of carbon dioxide and methane, respectively, vibrate? | The question is very specific and tractable, and its answer directly addresses the Specific Research Question (above). | "Insufficient" |

......