The Science Of Scientific Writing .Course Introduction. Overview : Content and Packaging : Enriched Blueprints : Compartmentalisation : Course Mechanics

OVERVIEW: The way to well-written science

PART I: Paragraphs and Sentences

SET A: Paragraphs: The Maps Behind Them

SET B: Paragraphs: Using Maps to Meet Readers' Expectations

SET C: Paragraphs with Something Extra: Points and Tails

SET D: The Generic Section: Expectations and Maps as Blueprints

SET E: Scientific Sections: The Methods and Results

SET F: Scientific Sections: The Discussion

SET G : Scientific Sections: The Introduction

SET H : Sentences

SET I : The Paper as a Whole

PART II: The Paper and its Sections

SET 1: Argument Parts

SET 2: Indicator Words

SET 4: Locating Arguments in Prose

SET 5: Rationale's Essay Planner

SET 6: Evidence in Arguments: Basis Boxes

Synthesis 1: Position-Early Paragraphs

Synthesis 2: Position-Final Paragraphs

Synthesis 3: Writing a Discussion I

Synthesis 4: Writing a Discussion II

How do we compartmentalise the information in a map?

The information in a text is compartmentalised in various ways, e.g.

- Section

- Paragraph

- Sentence

- Sentence parts

- Clause

- Phrase

For individual items on a map, or a cluster of items, nothing on a basic map tells us the type of compartment we should use.

For the Cats/Dogs example, we could package the whole argument as a single sentence, e.g.:

Cats make better pets than dogs because not only do they cost less to keep (cats eat less than dogs, and their accessories are smaller and cheaper) but they also require less time to maintain (they don't need daily walks, and they wash themslves).

or as various multi-sentence paragraphs, e.g.:

Cats make better pets than dogs. Firstly, cats cost less to keep, because a cat eats a lot less than the average dog, and the accessories you need to buy for a cat are smaller and cheaper. Secondly, cats require less time to maintain than dogs, because a cat does not need to be walked every day like a dog, and it can wash itself.

or even, in a very long-winded way, as three short paragraphs, e.g.:

I think that cats make better pets than dogs, because they cost less to keep than dogs, and also because they require less time to maintain.

As to the first point, that cats cost less to keep, it is obvious that cats eat a lot less than the average dog. Also, the accessories you need to buy for a cat are smaller and cheaper.

As to the second point, that cats require less time to maintain than dogs, a cat does not need to be walked every day like a dog, and it can wash itself.

Impact Factor: annotations can help us pick the right compartment type

We have already seen that once we have annotated an argument map with respect to argumentative strength and significance, we can make more informed decisions about how to sequence the parts of an argument in a text. These types of annotation can also help to some extent decide what type of compartment to package content in. This is because the different types of compartment have predictable effects on readers. For example, a given item will have more impact more if it is packaged as a paragraph rather than being compressed as a sentence within a paragraph. The list below shows the Impact Factors of the various text compartments, from high to low:

- Section

- Paragraph

- Sentence

- Sentence parts

- Clause

- Phrase

- Word

Here's a simple, subtle example of reducing the Impact Factor of the text in bold, by changing its sentence part type from Clause to Phrase (clauses have a verb, phrases do not).

Cats make better pets than dogs. Most importantly, cats usually cost less to keep, because cats typically eat less than dogs, and the accessories you need to buy for them are smaller and cheaper.

Cats make better pets than dogs. Most importantly, cats typically cost less to keep, because of their typically cheaper food, and because cats' accessories are smaller and cheaper than dogs'.

This is a very local type of decision but making global decisions about how to compartmentalise a map as a whole is difficult to do in a systematic way. One of the reasons for this is that attempts to improve local clarity may have adverse affects on global clarity. To understand this, and to get a sense of what compartmentalisation is really about. consider the following.

Cross Town Trip

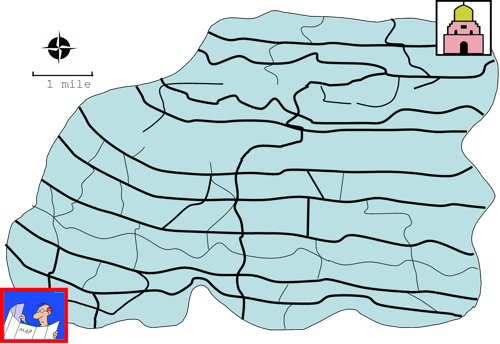

Imagine you, a local, are asked by a tourist how to get to the famous Lal Masjid on the other side of town. One way to do so would be to give a completely turn-by-turn account of the route. Considering the length of the route this might tax the tourist's memory. In writing, this might be the equivalent of writing an overly long paragraph - too much information in one go. The text is, in terms of paragraphing, uncompartmentalised.

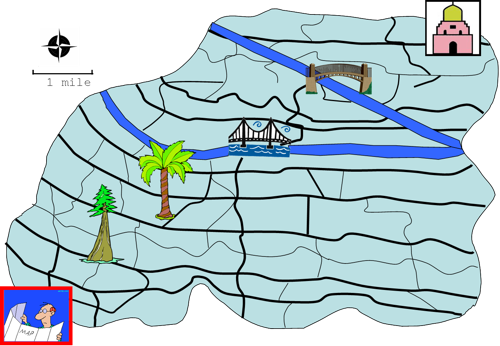

A better solution would be to suggest a series of landmarks along the way. The tourist only now has to remember four things, and as long as you give him some global pointers ("It's five miles north-west from here") he should not have too much trouble. In writing, each paragraph has one main "landmark" sentence, so this advice would be equivelent to a four or five paragraph text.

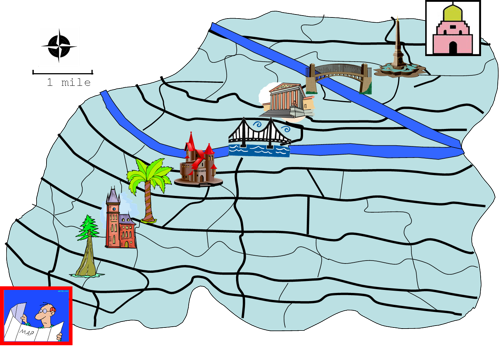

In this last depiction, your extensive knowledge of the city gets the tourist into problems. You provide eight landmarks, and while it may be better than none at all, it might still push the poor guy's mind into "attention-overload". This might equate to using eight paragraphs for a very short text, i.e. over-compartmentalisation.

......