The Science Of Scientific Writing .Course Introduction. Overview : Content and Packaging : Enriched Blueprints : Compartmentalisation : Course Mechanics

OVERVIEW: The way to well-written science

PART I: Paragraphs and Sentences

SET A: Paragraphs: The Maps Behind Them

SET B: Paragraphs: Using Maps to Meet Readers' Expectations

SET C: Paragraphs with Something Extra: Points and Tails

SET D: The Generic Section: Expectations and Maps as Blueprints

SET E: Scientific Sections: The Methods and Results

SET F: Scientific Sections: The Discussion

SET G : Scientific Sections: The Introduction

SET H : Sentences

SET I : The Paper as a Whole

PART II: The Paper and its Sections

SET 1: Argument Parts

SET 2: Indicator Words

SET 4: Locating Arguments in Prose

SET 5: Rationale's Essay Planner

SET 6: Evidence in Arguments: Basis Boxes

Synthesis 1: Position-Early Paragraphs

Synthesis 2: Position-Final Paragraphs

Synthesis 3: Writing a Discussion I

Synthesis 4: Writing a Discussion II

The Master Pattern

In this course we focus on two parts of the writing process: organising the content (use of mapping) and packaging (writing up) the content. In both activities, there is a single underlying principle at work, a central feaure of communication. Even if you stop this course after reading this section you will still have learned a valuable pronciple that you can apply in any type of writing (or even a seminar).

In most instances of ant organisational unit of a communication, start by providing a Frame of Reference, then follow up by Elaborating upon it.

The principle in a Map

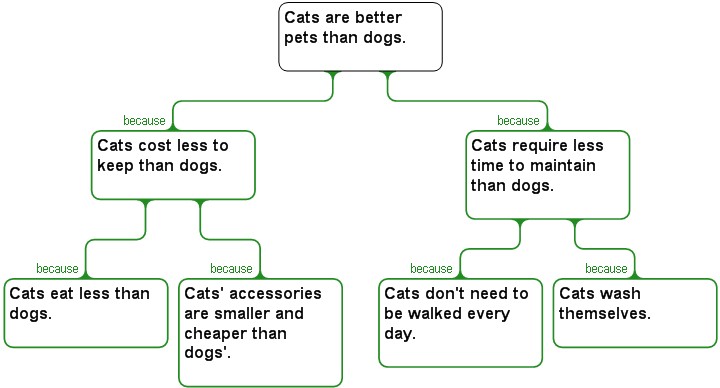

Let's see how it applies to a hierarchically organised map of a simple argument, arguing the contention: "Cats are better pets than dogs". A simliar map could be used to plan an explanation, or a description.

This argument map has three levels of structure:

1. The argument as a whole

2. The branches (two) of the argument

3. The individual contention and reasons (seven, expressed as sentences).

At the first level, the top box provides a claim which is supported by the remainder of the argument. At the second level, each branch is a sub-argument, identical in structure to the argument as a whole. When we look to each sentence we see they all follow the same pattern: the early part of the sentence is the sentence's brief grammatical subject - "cats" or a cat-related item, and the longer latter part (the predicate) tells us something new about "Cats" or the cat-related item.

So, at every level, we see the same pattern: First provide a frame of reference, then elaborate upon it.

The principle in Text

When we write up an argument (or any type of expository text) we cannot benefit from the explicit organisational cues we find in a map. In fact one of the defining features of text is that, unlike the al-at-once transmission of information we get with grapical forms communication, texts can only reveal their content in time, in a step-wise manner. Neverheless we can achive the same net result as amapby applying the Framework+Elaboration principle t ot he various components of a paper.

When we write up an argument (or any type of expository text) we cannot benefit from the explicit organisational cues we find in a map. In fact one of the defining features of text is that, unlike the al-at-once transmission of information we get with grapical forms communication, texts can only reveal their content in time, in a step-wise manner. Neverheless we can achive the same net result as amapby applying the Framework+Elaboration principle t ot he various components of a paper.

For an argument remember that the component structures were:

1. The argument as a whole2. The branches, sub-branhes etc

3. The individal contentions, reasons, obejctions, expressed as sentenes.

For a scientific paper

1. The paper as a whole

2. The sections (Introduction, Materials and Methods etc), and any sub-sections

3. The paragraphs

4. Sentences.

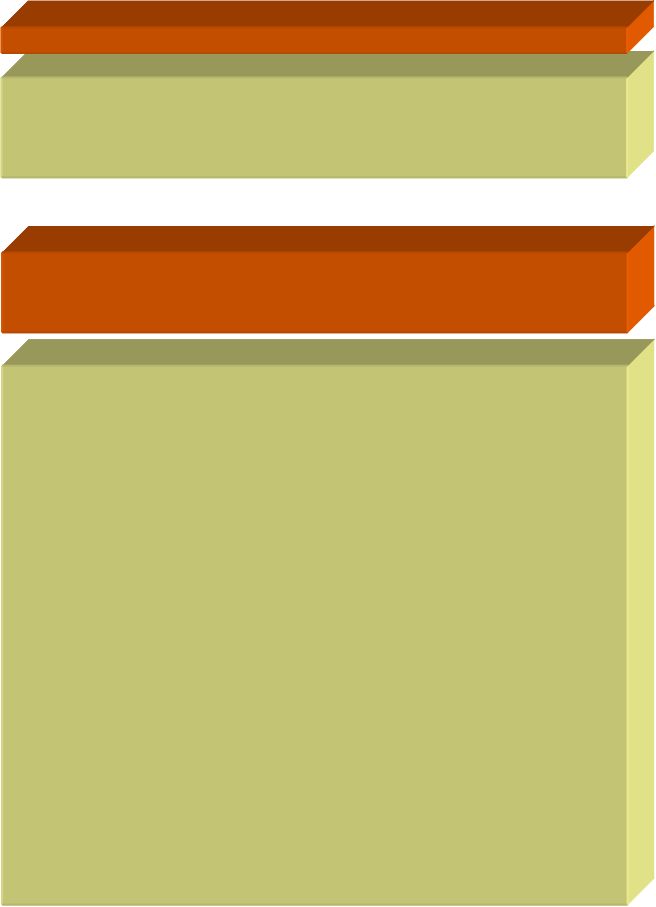

For the paper as a whole, the Introduction obviously provides the frame of reference for the rest of the paper.

When we look to individual sections, partcuarly the Introduction and Discussion, we find that their internal structure repeats that of the paper as a whole. The Introduction for example usually starts by providing a brief general view of a topic, and then a second part follows which details a more specific problem in the field. Discussions, especially long ones, often start with a paragraph that provides a guide to the discussion as a whole. So if we just consider the paper as consisting of the Introcution and Discussion, we see how the Framework + Elaboration pattern repeats itself:

Likewise when we look to subsections, paragraphs and sentences research into reading strategies tells us find that raeders expect these organisational units to basically employ the same pattern, particularly when sentences and paragraphs are long.

So we might illustrate the next "stage" of comparmentalisation of a text as in the third diagram in the series below:

We will of ocurse look in detail at how the principle is appied for paragraphs and sentences during the course. But as one example: if package the argument map used at the top of the page as a single paragraph, it might look something like this:

I think that cats make better pets than dogs. Firstly, cats cost less to keep, because a cat eats a lot less than the average dog, and the accessories you need to buy for a cat are smaller and cheaper. Secondly, cats require less time to maintain than dogs, a cat does not need to be walked every day like a dog, and it can wash itself.

The map could also be written up as three paragraphs, in a more long-winded way, but the example illustrates some additional tricks you might use if the content were actually more complex:

I think that cats make better pets than dogs, because they cost less to keep than dogs, and also because they require less time to maintain.

As to the first point, that cats cost less to keep, it is obvious that cats eat a lot less than the average dog. Also, the accessories you need to buy for a cat are smaller and cheaper.

As to the second point, that cats require less time to maintain than dogs, a cat does not need to be walked every day like a dog, and it can wash itself.

Complex text arguments must often rely on repetition, since the same content must do double service, first as a reason in support of an upper-level contention, and then as a contention itself, at the top of its own sub-argument.

Argument Maps and Text are Fractal in Nature

Argument maps and text both have a fractal structure,that is the patterning of the component parts is more or less similar to the patterning of the whole. Fractals are phenomena of the natural world, with common examples being snowflakes and many fern leaves. With regard to text, the fractal repetitiveness derives from the fact that at every level of organisation, the same challenge exists. How can the writer overcome the difficulties imposed by the step-wise, time-dependent unfolding of information, and provide the readers with the navigational cues equivalent to those they would get if the same information were packaged diagrammatcally.

Argument maps and text both have a fractal structure,that is the patterning of the component parts is more or less similar to the patterning of the whole. Fractals are phenomena of the natural world, with common examples being snowflakes and many fern leaves. With regard to text, the fractal repetitiveness derives from the fact that at every level of organisation, the same challenge exists. How can the writer overcome the difficulties imposed by the step-wise, time-dependent unfolding of information, and provide the readers with the navigational cues equivalent to those they would get if the same information were packaged diagrammatcally.

Why its not natural to follow this pattern

![]()

![]()

......