The Science Of Scientific Writing Set E Generic Sections Maps as Section Blueprints Exercise 1 Exercise 2 ImRaD Methods : Structure Methods: Coherence Exercise 3 Final Page .

OVERVIEW: The way to well-written science

PART I: Paragraphs and Sentences

SET A: Paragraphs: The Maps Behind Them

SET B: Paragraphs: Using Maps to Meet Readers' Expectations

SET C: Paragraph Coherence and Cohesion

SET D: Sentences

SET E: Scientific Sections (including Methods)

SET F: Scientific Sections: The Discussion

SET G : Scientific Sections: The Introduction

SET H : The Paper as a Whole

Set E: The "generic" Section, the IMRaD system and the Methods Section

The "generic" section: stepping up from the paragraph models

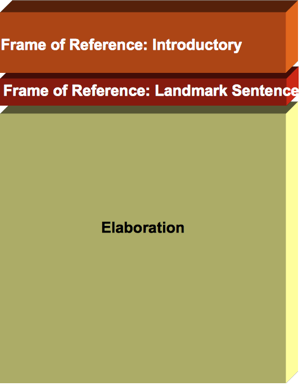

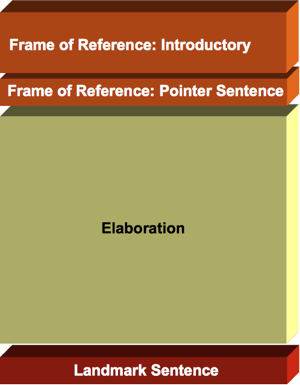

In Sets B and C you became familiar with the types of paragraphs that readers expect in expository text. All paragraphs of four or more sentences should consist of a Frame of Reference section, followed by an Elaboration. They should also have a Landmark Sentence which concludes the Frame of Reference section or the paragraph itself. In the latter case, the paragraph's Frame of Reference section should have a Pointer Sentence.

The two basic patterns of a paragraph

The only other important point to remember for the moment is that a paragraph should be coherent, and the main suggestion made in this regard so far is:

Any paragraph in a scientific paper should have one dominant (core) purpose (description/report, argument, explanation) and any non-core content should not overwhelm the core content.

Sections, essays, generic expository texts

The same two patterns above also underpin higher levels of writing as well, and in Set E we will begin by looking look at how to apply them to what I call the "generic" section. Of utmost importance is that you realise that not only does a section have the two main sub-sections (Frame of Reference + Elaboration) but that it must also have

- A Landmark Sentence for the section as a whole (always), and, if and only if the Landmark Sentence appears in the final paragraph,

- A Pointer Sentence for the section.

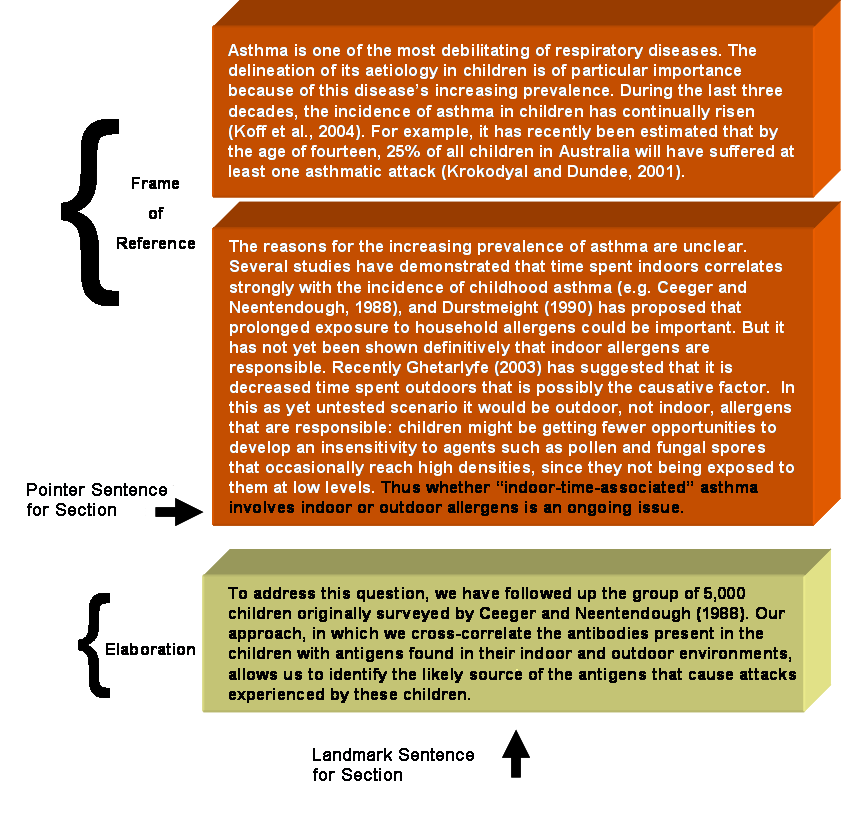

Below is a three-paragraph long example of a section following the second pattern above. It is an entire Introduction to a paper, and as is typical of such, its Frame of Reference section is relatively long.

Understanding the "generic section" will provide a foundation for understanding the traditional sections of a scientific paper: Introduction, Materials and Methods, Results, Discussion. These will be considered in detail as we proceed. While only the Discussion and Introduction follow the generic patterns explicitly, nevertheless, the two other section types often do so implicitly, and occasionally explicitly. For example, the Results section of this recent paper (doi:10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.018) begins with a Frame of Reference paragraph:

Studies from the 1970s (Chesney et al., 1974) showed that human platelets contain significant amounts of collagenase activity that could be released upon exposure to various agonists. More recent studies (Galt et al., 2002) identified the major platelet collagenase as MMP-1 and found that MMP-1 could prime the aggregatory response to other agonists and cause redistribution of the β3 integrins to the cell periphery; however, the mechanism of action of MMP-1 remained unknown. We set out to determine whether the pro-aggregatory effects of platelet MMP-1 were mediated by the PAR1 receptor.

Mastering the generic section patterns will also help you with other writing tasks. It is the standard structure expected of a scientific review (including a thesis literature review) and of the essays and term reports that are typical of Humanities courses. It can also be applied to many other types of non-creative writing (e.g. Statements of Purpose, cover letters for various applications).

A section must be coherent

Just as for a paragraphs, the other main expectation for a section is that it be coherent, and one aspect of coherence is the following:

Any section in a scientific paper should have one dominant (core) purpose (description/report, argument, explanation) and any non-core content should not overwhelm the core content.

In the asthma example above the core purpose is argument, focused on the (implied) claim:

We have the means to clarify whether indoor-time-associated asthma of children involves indoor or outdoor allergens, an important issue in understanding the aetiology of childhood asthma.

......