The Science Of Scientific Writing Set B Paragraphs: Intro to Readers' Expectations The Landmark What makes a landmark? Exercise 1 Quiz Landmark should appear early Exercise 2 A kick in the tail A plan for writing landmark-final paras Exercise 3 Exercise 4 Exercise 5 Exercise 6 Final Page.

OVERVIEW: The way to well-written science

PART I: Paragraphs and Sentences

SET A: Paragraphs: The Maps Behind Them

SET B: Paragraphs: Using Maps to Meet Readers' Expectations

SET C: Paragraph Coherence and Cohesion

SET D: Sentences

SET E: Scientific Sections (including Methods)

SET F: Scientific Sections: The Discussion

SET G : Scientific Sections: The Introduction

SET H : The Paper as a Whole

Set B: Readers' expectations of paragraphs, and how maps can help us to meet them

In Set A you learned how to create maps for the different styles of paragraphs used in scientific papers. These maps are useful tools for refining your ideas and for sharing those ideas with your immediate collaborators. But when you want to communicate more widely you need to be able to convert those maps into paragraphs. To do so you need to know how readers expect paragraphs to be organised, so that you can work with your readers, rather than against them. Readers can absorb written information more efficiently, and more accurately, if it is presented in the formats that they expect, either consciously or not.

In this Set we will look at the most common expectations of paragraph organisation, and at each point we will also see how easily we can use a pre-existing map to help us generate an acceptable paragraph. But first let us start by considering a verbal communication challenge that should make clear to you the whole point of using paragraphs in the first place. It should help you understand why every paragraph should have a "landmark".

Paragraphing is a navigational aid

"Too few"

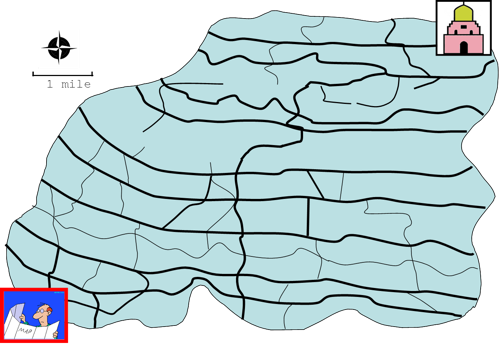

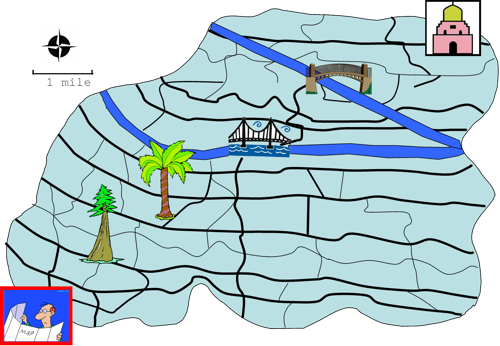

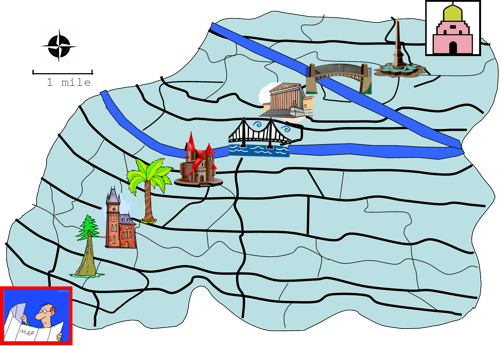

Imagine you, a local, are asked by a tourist how to get to the famous Lal Masjid on the other side of town (see map below). One way to do so would be to give a completely turn-by-turn account of the route. Considering the length of the route this would probably tax the tourist's memory. In writing, this might be the equivalent of writing an overly long paragraph - too much information in one go. The text is, in terms of paragraphing, uncompartmentalised. This was quite a common pattern in early scientific writings, for example try out this paragraph of 468 words written by Louis Pasteur in 1859 - for a modern reader it is quite a chore!

A better solution would be to suggest a series of landmarks, say four, along the way. The tourist now has to remember only a small number of things, and as long as you give him some global pointers ("It's five miles north-east from here") he should not have too much trouble. In writing, as we will see, each paragraph should have one main "landmark" sentence, so the advice for the tourist would be equivalent to a four paragraph text. The remainder of each paragraph would correspond, in our analogy, to the more detailed information you provide to the tourist about the part of the route between each set of two adjacent landmarks. "Sensible" paragraphing allows readers to easily navigate a potentially challenging text. For example, compare this version of the Pasteur paragraph with the original.

"Too many"

In this last depiction, your extensive knowledge of the city gets the tourist into problems. You provide eight landmarks, and while it may be better than none at all, it might still push the poor guy's mind into "attention-overload". This might equate to using eight paragraphs for a very short text, i.e. over-compartmentalisation. This is a very common pattern on internet sites.

Note: For most of this set we will focus on paragraphs with more than three sentences, because they are more difiicult to write. You might well think: "Well, why don't I only write short paragraphs?" If you did this, your readers may well have little trouble with each paragraph in isolation, but they would likely have major problems with the text as a whole, which will probably seem to lack cohesion. The most extreme example of this would be to make each sentence of the paper a separate paragraph!

3rd paragraph of Pasteur’s “The Physiological Theory of Fermentation”

Note: the word "must" in this report is a specialized term from wine-making and refers to unfermented grape juice.

The least reflection will suffice to convince us that the alcoholic ferments must possess the faculty of vegetating and performing their functions out of contact with air. Let us consider, for instance, the method of vintage practised in the Jura. The bunches are laid at the foot of the vine in a large tub, and the grapes there stripped from them. When the grapes, some of which are uninjured, others bruised, and all moistened by the juice issuing from the latter, fill the tub--where they form what is called the vintage--they are conveyed in barrels to large vessels fixed in cellars of a considerable depth. These vessels are not filled to more than three-quarters of their capacity. Fermentation soon takes place in them, and the carbonic acid gas finds escape through the bunghole, the diameter of which, in the case of the largest vessels, is not more than ten or twelve centimetres (about four inches). The wine is not drawn off before the end of two or three months. In this way it seems highly probable that the yeast which produces the wine under such conditions must have developed, to a great extent at least, out of contact with oxygen. No doubt oxygen is not entirely absent from the first; nay, its limited presence is even a necessity to the manifestation of the phenomena which follow. The grapes are stripped from the bunch in contact with air, and the must which drops from the wounded fruit takes a little of this gas into solution. This small quantity of air so introduced into the must, at the commencement of operations, plays a most indispensable part, it being from the presence of this that the spores of ferments which are spread over the surface of the grapes and the woody part of the bunches derive the power of starting their vital phenomena. This air, however, especially when the grapes have been stripped from the bunches, is in such small proportion, and that which is in contact with the liquid mass is so promptly expelled by the carbonic acid gas, which is evolved as soon as a little yeast has formed, that it will readily be admitted that most of the yeast is produced apart from the influence of oxygen, whether free or in solution. We shall revert to this fact, which is of great importance. At present we are only concerned in pointing out that, from the mere knowledge of the practices of certain localities, we are induced to believe that the cells of yeast, after they have developed from their spores, continue to live and multiply without the intervention of oxygen, and that the alcoholic ferments have a mode of life which is probably quite exceptional, since it is not generally met with in other species, vegetable or animal.

Go back to where you came from

Revision of 3rd paragraph of Pasteur’s “The Physiological Theory of Fermentation”

(Nothing has been added to the original, but the text has been compartmentalised into three "logical units" and the likely "landmark" sentences shown in bold. Note that we can get a good sense of the overall flow just by reading the landmark sentences).

The least reflection will suffice to convince us that the alcoholic ferments must possess the faculty of vegetating and performing their functions out of contact with air. Let us consider, for instance, the method of vintage practised in the Jura. The bunches are laid at the foot of the vine in a large tub, and the grapes there stripped from them. When the grapes, some of which are uninjured, others bruised, and all moistened by the juice issuing from the latter, fill the tub--where they form what is called the vintage--they are conveyed in barrels to large vessels fixed in cellars of a considerable depth. These vessels are not filled to more than three-quarters of their capacity. Fermentation soon takes place in them, and the carbonic acid gas finds escape through the bunghole, the diameter of which, in the case of the largest vessels, is not more than ten or twelve centimetres (about four inches).

The wine is not drawn off before the end of two or three months. In this way it seems highly probable that the yeast which produces the wine under such conditions must have developed, to a great extent at least, out of contact with oxygen. No doubt oxygen is not entirely absent from the first; nay, its limited presence is even a necessity to the manifestation of the phenomena which follow. The grapes are stripped from the bunch in contact with air, and the must which drops from the wounded fruit takes a little of this gas into solution. This small quantity of air so introduced into the must, at the commencement of operations, plays a most indispensable part, it being from the presence of this that the spores of ferments which are spread over the surface of the grapes and the woody part of the bunches derive the power of starting their vital phenomena.

This air, however, especially when the grapes have been stripped from the bunches, is in such small proportion, and that which is in contact with the liquid mass is so promptly expelled by the carbonic acid gas, which is evolved as soon as a little yeast has formed, that it will readily be admitted that most of the yeast is produced apart from the influence of oxygen, whether free or in solution. We shall revert to this fact, which is of great importance. At present we are only concerned in pointing out that, from the mere knowledge of the practices of certain localities, we are induced to believe that the cells of yeast, after they have developed from their spores, continue to live and multiply without the intervention of oxygen, and that the alcoholic ferments have a mode of life which is probably quite exceptional, since it is not generally met with in other species, vegetable or animal.

Go back to where you came from

......