The Science Of Scientific Writing .Course Introduction. Overview : Content and Packaging : Enriched Blueprints : Compartmentalisation : Course Mechanics

OVERVIEW: The way to well-written science

PART I: Paragraphs and Sentences

SET A: Paragraphs: The Maps Behind Them

SET B: Paragraphs: Using Maps to Meet Readers' Expectations

SET C: Paragraph Coherence and Cohesion

SET D: Sentences

SET E: Scientific Sections (including Methods)

SET F: Scientific Sections: The Discussion

SET G : Scientific Sections: The Introduction

SET H : The Paper as a Whole

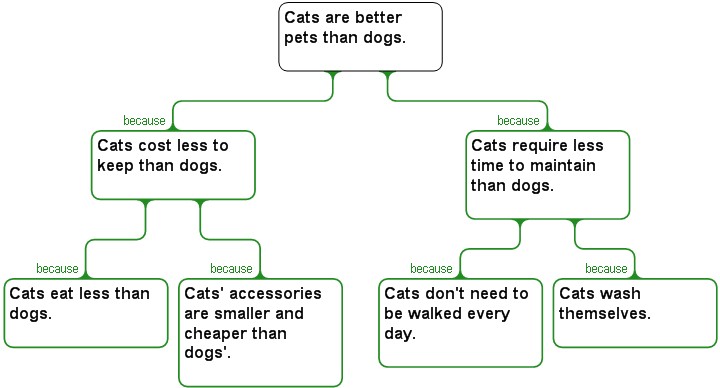

Within a branch, which items get written up first?

If we consider the entire left-hand branch, the map does not tell us whether to start or end with the main claim "Cats make better pets than dog". Each of the versions below is equally possible:

1. A cat eats a lot less than the average dog, and the accessories you need to buy for a cat are smaller and cheaper. Therefore, cats cost less to keep than dogs, and this supports the idea that cats make better pets than dogs.

2. Cats make better pets than dogs, because a cat costs less to keep. For example, a cat eats a lot less than the average dog, and its accessories are smaller and cheaper.

* Organising principle: degree of "concreteness"

The question above is influenced by another consideration: when working within a branch, to what degree is a reason concrete and open to easy substantiation? In arguments at least, we do not need to add any further annotations to a map to make it clear which are the more concrete items. They are usually found nearer the base of a branch, e.g. "Cats wash themselves" is a more concrete and universally true item of information than "Cats require less time to maintain than dogs". Thus, once we have decided in which direction we want to work in, we can then work out the right sequencing directly from the map. Compare the evidence-first versus evidence-last versions below.

1. A cat eats a lot less than the average dog, and the accessories you need to buy for a cat are smaller and cheaper. Therefore, cats cost less to keep than dogs, and this supports the idea that cats make better pets than dogs.

2. Cats make better pets than dogs, because a cat costs less to keep. For example, a cat eats a lot less than the average dog, and its accessories are smaller and cheaper.

To most people the first version will sound more "cautious" because to a certain extent it lets the readers come to the conclusion themselves. It is therefore a style you might want to use in the Discussion section, if you are trying to create the impression of being a careful scientist. The more direct style of the second version might be more suited to an Abstract.

![]()

![]()

......