The Science Of Scientific Writing .Course Introduction. Overview : Content and Packaging : Enriched Blueprints : Compartmentalisation : Course Mechanics

OVERVIEW: The way to well-written science

PART I: Paragraphs and Sentences

SET A: Paragraphs: The Maps Behind Them

SET B: Paragraphs: Using Maps to Meet Readers' Expectations

SET C: Paragraph Coherence and Cohesion

SET D: Sentences

SET E: Scientific Sections (including Methods)

SET F: Scientific Sections: The Discussion

SET G : Scientific Sections: The Introduction

SET H : The Paper as a Whole

Our basic blueprints can be "enriched"

As blueprints for writing text, the basic hierarchical maps we have considered so far are not as all-determining as those used for home-building. They will provide strong clues for some aspects of the organisation of the text version, but we will need to look to other considerations to help us go the whole way. On this and the next few pages we will briefly look at:

Enriched maps can help guide text composition

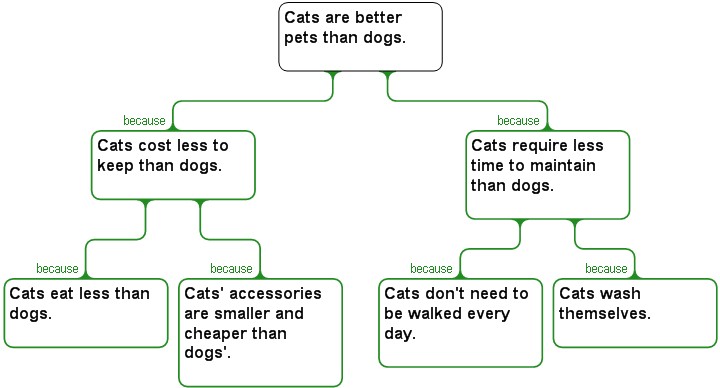

A basic map does not help us when making many of the decisions that lie behind writing text that is polished. This problem becomes more and more evident as the length of the text increases: the problem of the whole, as it were, is then more than the problem of the parts. It is important therefore to consider these decisions, and how an "enriched" map can help us. Using the Cats/Dogs argument as a test system, we will look at three important decisions:

- Which branch do we write up first?

- Within a branch, which items get written up first?

- How do we compartmentalise the information in the map?

Which branch do we write up first?

In the Cats/Dogs example, the map does not tell us which of the two major branches to cover first. Ths is important because in a written argument with multiple lines of evidence readers typically expect that the sequence of their presentation will demonstrate adherence to some sort of organising principle that has a pervasive influence on the text.

There are many types of organising principles, and they are also expected in other, non-argumentative, types of text. Let us first look at two that are relevant to arguments, and then some others that may be applicable to a description.

* Organising principle: degree of argumentative strength

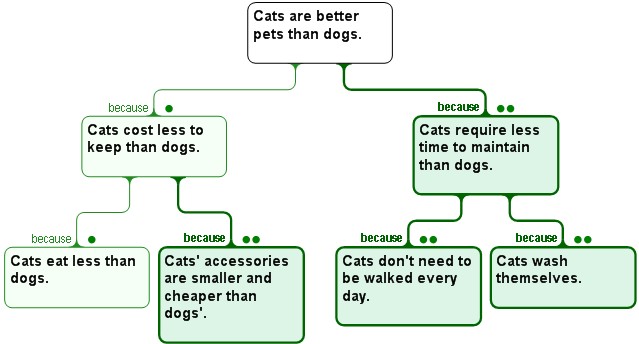

Probably the most common organising principle in arguments involves organising the sequence according to the comparative argumentative strengths of the lines of reasoning: we often start or end with the strongest line of evidence, but rarely (if there are more than two lines) do we put it in the middle. Therefore, we can enrich our map by adding visual markers of the relative argumentative strength, that can then help us make decisions about text organisation.

In the map below we have decided that the evidence "Cats eat less than dogs" is not so strong, e.g. because some dog breeds are smaller than cats. Accordingly, usng the system of the argument mapping software used here (Rationale), that item only gets one "dot" and is shaded light green. Its "weakness" also infects the claim it is meant to support ("Cats cost less to keep than dogs").

If we present the strongest line of evidence first (as is probably the default pattern in standard scientific text), we might get something like this:

Cats make better pets than dogs. Most clearly, cats require less time to maintain than dogs, because a cat does not need to be walked every day, and it can wash itself. Further, cats often cost less to keep, because the accessories you need to buy for them are smaller and cheaper, and cats, for the most part, eat less than dogs.

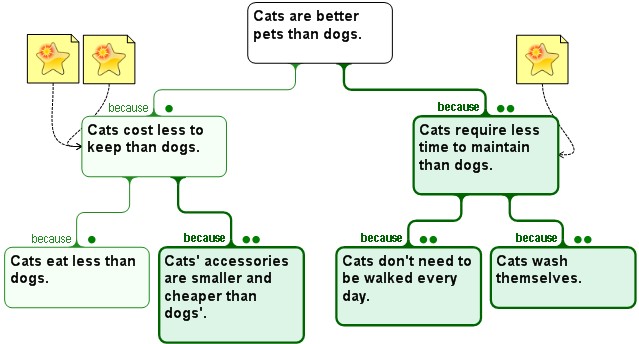

* Organising principle: degree of argumentative significance

Another important consideration in sequencing the parts of an argument is how significant a line of reasoning would be if it were true. Considerations of audience interest influence some scientists in their thinking about where to position their discussion of various lines of evidence. In particular a "risk-loving" scientist might put the most "interesting" line of evidence in the position where he or she think it will be noticed most, even if that evidence is rather weak.

Let's imagine you are also the bold type and you are evaluating the Cats/Dogs argument. You think that while the left-hand branch presents a weaker argument the particular pet "burden" it addresses is the one of greatest concern to pet owners, so you give it two "stars of significance".

And you decide, risk-taker that you are, that you will write it up putting the most "significant", not the strongest, line of evidence first, with some extra wording to indicate you do have some concerns about strength of evidence (usually, typically):

Cats make better pets than dogs. Most importantly, cats usually cost less to keep, because cats typically eat less than dogs, and the accessories you need to buy for them are smaller and cheaper. Also, cats clearly require less time to maintain than dogs, because a cat does not need to be walked every day, and it can wash itself.

* Organising principle: "real-world" relationships

In the descriptive, non-argumentative text typical of the Materials and Methods and Discussion sections of a paper, the most common organising principles relate to graded real-world attributes of the items, for example:

- Size

- Weight

- Frequency

- Duration

- Chronological sequence

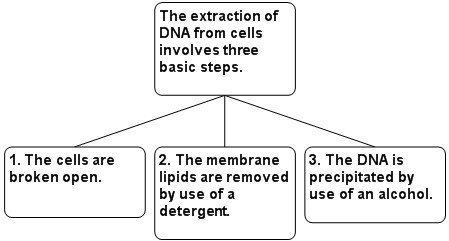

The chronological sequence of research activities is commonly used as the overall organising principle of the Materials and Methods section. For example, coming back to our DNA extraction map, it is important to know that the three steps must be done in a particular order, so we could annotate the map as below:

......