The Science Of Scientific Writing Set B Paragraphs: Intro to Readers' Expectations First Three Expectations Exercise 1 Quiz A Fourth Expectation: Coherence Paragraph flexibility: explicit and implicit texts Exercise 2 Final Page.

OVERVIEW: The way to well-written science

PART I: Paragraphs and Sentences

SET A: Paragraphs: The Maps Behind Them

SET B: Paragraphs: Using Maps to Meet Readers' Expectations

SET C: Paragraphs with Something Extra: Points and Tails

SET D: The Generic Section: Expectations and Maps as Blueprints

SET E: Scientific Sections: The Methods and Results

SET F: Scientific Sections: The Discussion

SET G : Scientific Sections: The Introduction

SET H : Sentences

SET I : The Paper as a Whole

PART II: The Paper and its Sections

SET 1: Argument Parts

SET 2: Indicator Words

SET 4: Locating Arguments in Prose

SET 5: Rationale's Essay Planner

SET 6: Evidence in Arguments: Basis Boxes

Synthesis 1: Position-Early Paragraphs

Synthesis 2: Position-Final Paragraphs

Synthesis 3: Writing a Discussion I

Synthesis 4: Writing a Discussion II

Paragraphs are more flexible than maps: explicit versus implicit texts

In Set A we introduced four types of map that you can use to plan the paragraphs of a scientific paper. In this set you have seen how these can be used to generate text versions of mapped arguments, reports, descriptions and explanations. When working with maps you were encouraged to work strictly within one mode of exposition, and not to mix, for example, a report or explanation with an argument (in the map's core content). This disciplined approach will result in clearer thinking about the content, and a map that is easily followed by your collaborators.

But when it comes to writing, things are more fluid. There is no doubt that one can generate acceptable, and lucid, paragraphs by explicitly working from the map. But it does not mean that such an explicit relationship between map and text is an absolute requirement for a paragraph to be lucid. This is most clearly seen in arguments, where one will find many sophisticated persuasive devices employed, often referred to collectively as rhetoric. Since readers often feel uncomfortable if the writer seems bent on converting them to his or her cause, one of the most common strategies of rhetoric is to deflect attention away from the argumentative content. The argument is still there, but rather than being explicit it is now presented indirectly( i.e. implicitly), and if written with skill, it will be as lucid as any direct version.

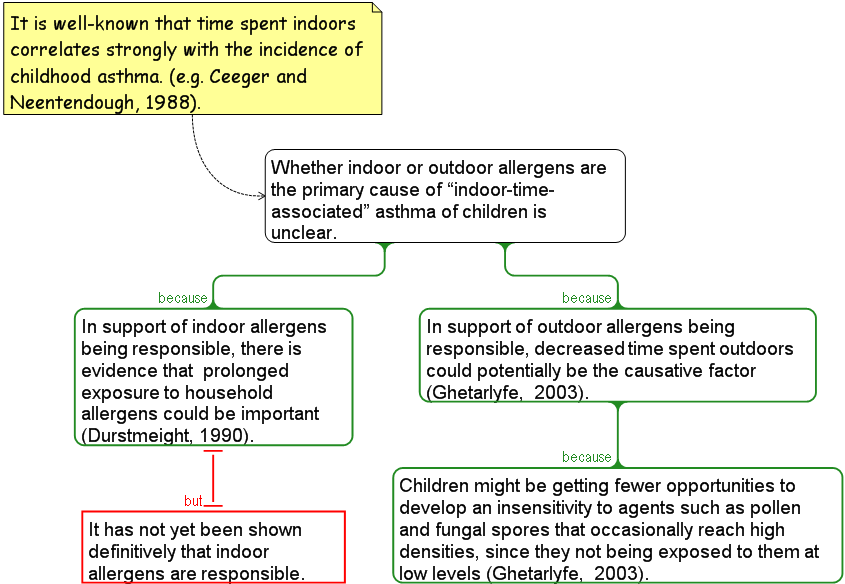

Implicit arguments are very common in the Introduction section of a scientific paper. Compre the following argument map, with its text version (below the map) written up in the style typical of an Introduction:

The reasons for the increasing prevalence of asthma are unclear. Ceeger and Neentendough (1988) have demonstrated that time spent indoors correlates strongly with the incidence of childhood asthma. Durstmeight (1990) later provided some evidence that prolonged exposure to household allergens could be important, but it has not yet been shown definitively that indoor allergens are responsible. Recently, Ghetarlyfe (2003) has suggested that it is decreased time spent outdoors that is possibly the causative factor. In this as yet untested scenario it would be outdoor, not indoor, allergens that are responsible: children might be getting fewer opportunities to develop an insensitivity to agents such as pollen and fungal spores that occasionally reach high densities, since they are not being exposed to them at low levels. Thus whether indoor-time-associated asthma of children involves indoor or outdoor allergens remains an ongoing issue.

There are several changes in emphasis between the map and the text version: one of the most important rhetorical shifts is that in the text version the researchers behind all the work have been made much more prominent. Thus instead of it being an out-and-out argument, it becomes a description of events, with the argument in the background (i.e. implied). The readers' attention is partly deflected by the narrative flow. The other shift of course is that the specific point being argued is not fully stated until the very end (a structure we will look at in Set C), thus "letting" the readers feel like they are arriving at this conclusion themselves.

The specifics of this particular example are not as important as the general point: if you find it tricky to determine the purpose of a paragraph, this might be the result of a skilled writer deflecting your attention away from a somewhat hidden agenda!

......