The Science Of Scientific Writing Set B Paragraphs: Intro to Readers' Expectations First Three Expectations Exercise 1 Quiz A Fourth Expectation: Coherence Paragraph flexibility: explicit and implicit texts Exercise 2 Final Page.

OVERVIEW: The way to well-written science

PART I: Paragraphs and Sentences

SET A: Paragraphs: The Maps Behind Them

SET B: Paragraphs: Using Maps to Meet Readers' Expectations

SET C: Paragraphs with Something Extra: Points and Tails

SET D: The Generic Section: Expectations and Maps as Blueprints

SET E: Scientific Sections: The Methods and Results

SET F: Scientific Sections: The Discussion

SET G : Scientific Sections: The Introduction

SET H : Sentences

SET I : The Paper as a Whole

PART II: The Paper and its Sections

SET 1: Argument Parts

SET 2: Indicator Words

SET 4: Locating Arguments in Prose

SET 5: Rationale's Essay Planner

SET 6: Evidence in Arguments: Basis Boxes

Synthesis 1: Position-Early Paragraphs

Synthesis 2: Position-Final Paragraphs

Synthesis 3: Writing a Discussion I

Synthesis 4: Writing a Discussion II

We will start by looking at three of the most obvious expectations of paragraph organisation.

(1) A paragraph should provide an early frame of reference, followed by an elaboration

Readers expect that a (long) paragraph will generally have two main parts, whose roles are shown in the diagrams below:

By and large the expectation is that in most paragraphs the Frame of Reference part will also be shorter than the Elaboration (hence the second diagram), but this is not expected for every paragraph.

The paragraph below has a three-sentence Frame of Reference section (in bold) followed by a five-sentence Elaboration:

We now move away from the focus on flowering times. The preliminary trapping experiments indicated that pollination of most plant species in the study area was insect-mediated. In our efforts to identify possible pollinators of Lantana camara, four species of butterflies were identified. The most frequently seen species was the Common Jay, Graphium doson. The Common Jay was also the smallest of the observed species, with a wingspan of 70-80mm. Slightly less frequent than the Common Jay was the Crimson Rose, Pachliopta hector. The Southern Birdwing (Troides minos), the largest of the butterflies observed (wingspan 140-190mm), was only an occasional visitor to the site. The least frequently seen species was the Common Bluebottle, Graphium sarpedon.

(2) The frame of reference section should be between 1-3 sentences long; and (3) it should conclude with a "framing" sentence

Within the Frame of Reference section (FOR) readers have further, more detailed expectations. First, they expect that the FOR will not extend beyond three sentences (in fact, most paragraphs have a single-sentence FOR). If readers get to the fourth sentence without experiencing an obvious switch to elaboration, they get frustrated, wondering what is the paragraph's point. Second, they expect the final sentence of the FOR to have a definitive quality, such that it can independently, or almost independently, provide a frame of reference for the rest of the paragraph.

Thus, looking once more at the paragraph used above, if we remove the first and second sentences, then what was the third sentence now serves well enough as a frame of reference for the paragraph:

In our efforts to identify possible pollinators of Lantana camara, four species of butterflies were identified. The most frequently seen species was the Common Jay, Graphium doson. The Common Jay was also the smallest of the observed species, with a wingspan of 70-80mm. Slightly less frequent than the Common Jay was the Crimson Rose, Pachliopta hector. The Southern Birdwing (Troides minos), the largest of the butterflies observed (wingspan 140-190mm), was only an occasional visitor to the site. The least frequently seen species was the Common Bluebottle, Graphium sarpedon.

I will refer to the sentence that plays this critical role in a paragraph as the framing sentence.

How maps can help us meet these three expectations

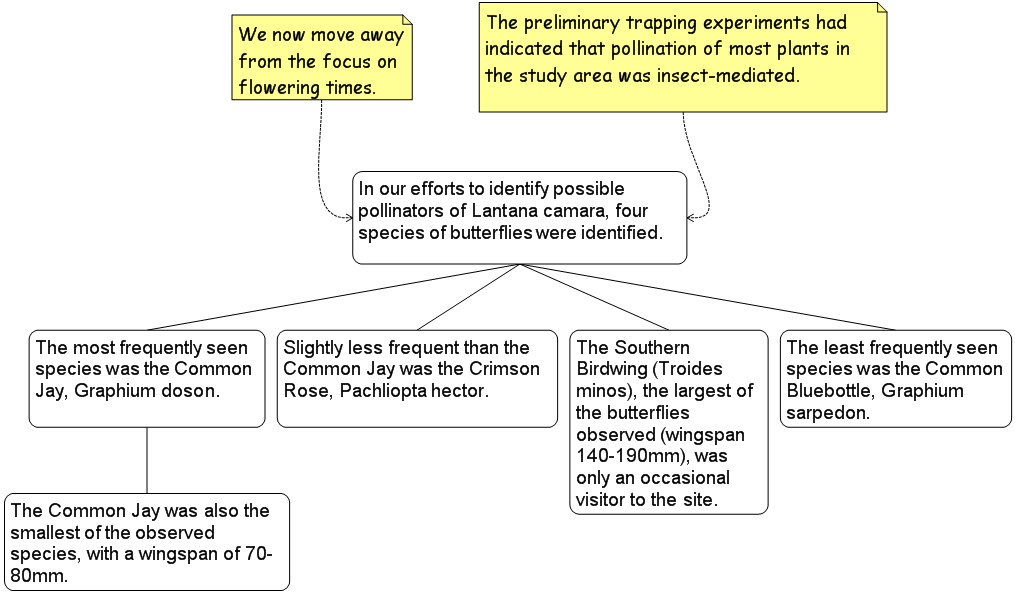

If we consider a map that represents the content of the paragraph above, it's not hard to see that once we have a map, there's not much more to think about in writing up a paragraph that meets the expectations we have considered on this page:

It's clear that:

- The framing sentence of the paragraph is the sentence that appears in the top box of the core content of the map

- The rest of the Frame of Reference section consists of any non-core content boxes that would seem to fit best above (i.e. before) the top box content

- The Elaboration of the paragraph is the remainder of the map, including both its core and any non-core content.

Of course if the top box of your map has more than two boxes of non-core content atatched to it, then you have to think of ways of reducing that content to two sentences: otherwise the framing sentence will be pushed to the paragraph's fourth sentence or beyond.

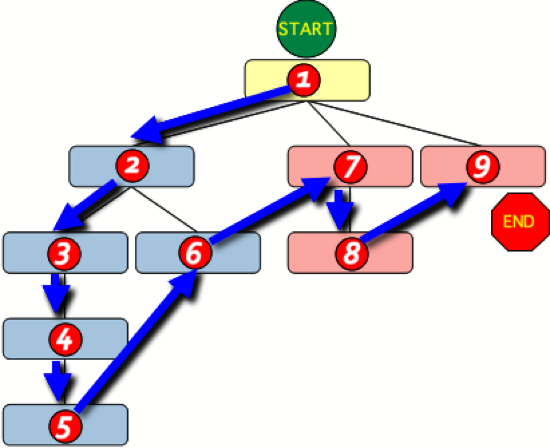

We also need some agreed-upon rules that help us translate the organisation of boxes into a sequence of elements in the paragraph. Most people find the suggested pattern below an intuitive one to follow.

I used the word "element" instead of sentence, because while we always use sentences in map boxes, we may compress those sentences into parts of sentences when we come to write up the paragraph. For example, the five-sentence Elaboration of the paragraph used above could be compacted into three sentences, making the paragraph less "long-winded":

We now move away from the focus on flowering times. The preliminary trapping experiments indicated that pollination of most plant species in the study area was insect-mediated. In our efforts to identify possible pollinators of Lantana camara, four species of butterflies were identified. The most frequently seen species, the Common Jay, Graphium doson, was also the smallest of the observed species, with a wingspan of 70-80mm. Slightly less frequent than the Common Jay was the Crimson Rose, Pachliopta hector. The Southern Birdwing (Troides minos), the largest of the butterflies observed (wingspan 140-190mm), was only an occasional visitor to the site, and its rarity was exceeded only by the Common Bluebottle, Graphium sarpedon.

......