The Science Of Scientific Writing Set D Expectations of the Generic Section Maps for Sections Exercise 1 Exercise 2 Final Page .

OVERVIEW: The way to well-written science

PART I: Paragraphs and Sentences

SET A: Paragraphs: The Maps Behind Them

SET B: Paragraphs: Using Maps to Meet Readers' Expectations

SET C: Paragraphs with Something Extra: Points and Tails

SET D: The Generic Section: Expectations and Maps as Blueprints

SET E: Scientific Sections: The Methods and Results

SET F: Scientific Sections: The Discussion

SET G : Scientific Sections: The Introduction

SET H : Sentences

SET I : The Paper as a Whole

PART II: The Paper and its Sections

SET 1: Argument Parts

SET 2: Indicator Words

SET 4: Locating Arguments in Prose

SET 5: Rationale's Essay Planner

SET 6: Evidence in Arguments: Basis Boxes

Synthesis 1: Position-Early Paragraphs

Synthesis 2: Position-Final Paragraphs

Synthesis 3: Writing a Discussion I

Synthesis 4: Writing a Discussion II

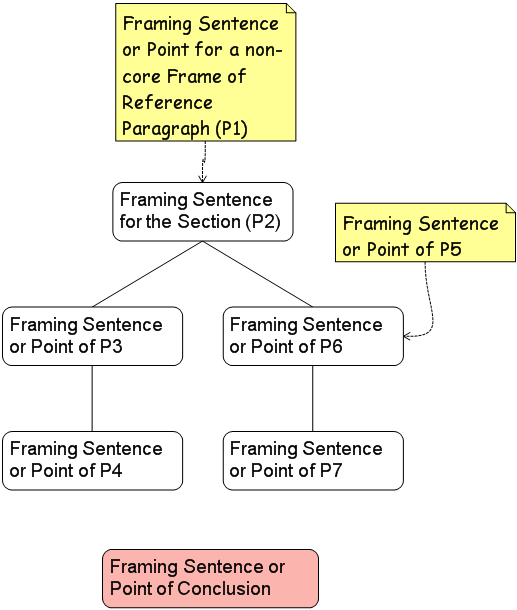

The map as a blueprint for a generic section

Some of you might feel that paragraphs are short enough to write up without the assistance of a map, but sections obviously present a greater challenge, and some sort of "blueprint" or outline is invaluable. And now that you understand how to make a map for a paragraph, a section map is a piece of cake!

In constructing a map for a section, we use one box per paragraph, and in each box we put:

- One paragraph's Framing Sentence, if the paragraph does not have a concluding Point or,

- One paragraph's Point Sentence, if the paragraph does have a concluding Point

Note that for any paragraph that has both Framing and Point Sentences, the Point Sentence will always "trump" the Framing Sentence, and be put in the box for that paragraph.

Below is an illustrative map for a section of eight paragraphs, two of which are non-core, and one of which is a Conclusion. The branching pattern shown is arbitrary.

The sentences of a section map must tell a coherent, single-purpose story

One of the easiest ways to improve the quality of your writing is to make sure that the sentences that you put in the boxes of a section map tell a coherent "story". When your collaborators read the map they should be able to make sense of it. And just as a paragraph map should have a core that has a single purpose (description/report. argument, explanation), so should your section map.

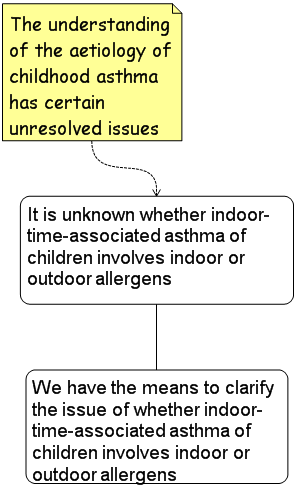

If we were making up a map for the Introduction to the asthma paper (on previous page), we might start with something like this:

Notice that as we work our way through the map, adjacent boxes share key words: asthma, childhood, children, indoor, outdoor etc. Inexperienced writers often feel that they should never repeat important words, and anxious that the reader will be bored, they head to their thesaurus to hunt down different-sounding synonyms. But in reality, if you use exactly the same terms in the key sentences of your writing (i.e. the Framing and Point Sentences), you will create a sense of continuity and coherence in the text.

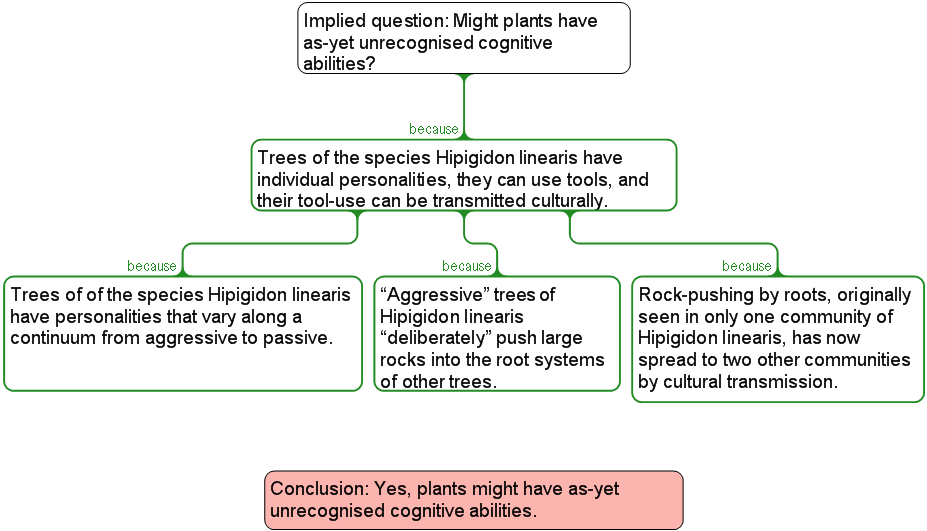

Below is a map for a six-paragraph essay that you have not seen before. Read the map first, and then check it against the essay further below. The sentences in the essay that correspond to those in the boxes of the map are shown in bold. Did the map provide an adequate sense of the structure and purpose of the essay?

Do Plants Think?

The recognition that animals share many of the cognitive capabilities once thought unique to humans has only occurred recently. We now know that some birds and mammals use tools, plan ahead, have an advanced sense of self, exhibit individual personalities, and transmit cultural knowledge. It has been argued that the long delay in our detection of “human” qualities in other species reflects less upon animal behaviour being particularly cryptic, but more upon our highly anthropocentric perspective of the natural world. A recent study is now indicating that these blinkers may have prevented us from appreciating cognitive abilities not only in the animal world, but, extraordinarily, amongst our plant cousins as well.

In their recent Scienz (2009) paper, Menker and Mercer provide the first report on a three-decade study of three communities of Hipigidon linearis, a tree that grows only in the highlands of New Guinea. They chose these communities because they thought their isolated location would allow for the first truly longitudinal study of the dynamic interaction between the growth of individual trees and the stand as a whole. The growth of every tree in these communities was monitored, both above-ground, using a combination of visual assessment and photography, and under-ground, using Ground Penetrating Radar. They measured the growth characteristics of the stand as a whole using aerial photography. Their observations however have led them to make some very unexpected conclusions: that trees of Hipigidon linearis have individual personalities, that they can use tools, and that this tool-use can be transmitted culturally, all examples of what they call “plant cognition”.

According to the authors, trees of Hipigidon linearis have personalities that vary along a continuum from aggressive to passive. This classification is based on correlations amongst a suite of five characteristics, all of which determine how likely a tree is to successfully invade another tree’s territory, and to resist invasion of its own. Aggressive trees (1) extend their branches into other trees’ crowns, and can support growth of such branches even though they are highly shaded; (2) drop branches from near the top of their canopy onto neighbouring trees (3) drop leaves with a high content of a chemical that inhibits the growth of other trees in their vicinity (4) extend their roots into the root systems of other trees (5) push large underground rocks into the root systems of other trees. The authors propose that one might expect variation with respect to any one of these characteristics individually, but the correlated nature of five features all related to territorial success is remarkable.

The idea that the trees exhibit tool-use is based upon the observation, mentioned above, of “aggressive” trees “deliberately” pushing large rocks into the root systems of other trees. The authors argue that this is not just the passive movement of rocks by roots. Rocks are apparently pushed preferentially towards neighbouring trees, a feat that involves roots reorienting their normal radial growth patterns by up to 90 degrees. Rocks are never pushed in a direction that leads into an area without another tree. Interestingly, the large roots that push rocks form secondary offshoots that form a basket around a rock, and this apparently increases the efficiency of force transmission.

Rock-pushing was originally seen in only one of the three communities, but its deployment has now spread to the other two communities by what the authors claim is cultural transmission of a skill. When they initially noticed rock-pushing in the first community, they noted that the behaviour was not shared by all aggressive trees, but only by seven individuals. Moreover, these trees were all clustered together. Intrigued by this, the authors transplanted one rock-pushing tree to each of the other communities, and within a year the aggressive trees around the transplanted trees themselves began to push rocks. DNA analysis failed to reveal any change in the genetic make-up of the trees that had acquired the new behaviour, leading to the conclusion that the skill is transmitted “culturally”. The authors cannot yet suggest a mechanism by which this might occur.

Menker and Mercer argue that these extraordinary observations should awaken a whole new awareness about trees. They claim that these trees are not freaks of nature but that, as somewhat extreme cases, they point to less obvious cognitive capabilities shared by all trees. They believe that we are made blind to their abilities by the vastly different time-scales that govern the lives of humans and trees. They say: “If we could watch the life of a tree speeded up a hundred times, and if we were attuned to the subtleties of trees' sedentary life-style, we would probably be amazed at how well they plan for the future, how much they live like a community, and how their personalities are as individual as their shapes”. And many of us are cannot wait to hear what they think about dogs.

......