The Science Of Scientific Writing Set F The Discussion: Answers Two Main Parts Maps for Discussions Exercise 1 Final Page .

OVERVIEW: The way to well-written science

PART I: Paragraphs and Sentences

SET A: Paragraphs: The Maps Behind Them

SET B: Paragraphs: Using Maps to Meet Readers' Expectations

SET C: Paragraph Coherence and Cohesion

SET D: Sentences

SET E: Scientific Sections (including Methods)

SET F: Scientific Sections: The Discussion

SET G : Scientific Sections: The Introduction

SET H : The Paper as a Whole

The two main parts of the Discussion

The Discusion typically consists of two main parts, defined by the type of question being addressed.

- Part 1, which is essential, discusses how the Results (i.e. the answers to the Research Objectives) help us to answer the Specific Research Question/s.

- Part 2, which is optional, starts with the answers to the SRQs from Part 1, and discusses how they how help us to answer the the General Research Question, or to better understand the Research Area.

It might seem self-evident that it necessary to present the content of Part 1 before that of Part 2, but as authors we can get so carried away by the broader implications of our work that we can end up reversing the order, or even more extremely, omitting Part 1 altogether! By putting the Part 1 content first, we demonstrate to our readers that we are "hard-nosed" scientists who build upon a solid evidence-based foundation. We are also presenting the bigger blocks of content in the sequence that will often be used with smaller blocks (e.g. sub-sections/paragraphs) of Part 1 as well. That is, we typically present content that is less speculative content before that of a more speculative nature. In the case of Part 1 versus Part 2, Part 2 is always more speculative because it deals with questions of a more general, less tractable nature. Within Part 1, some conclusions will be more speculative because the evidence to support them is weaker. However as we will see on the next page, sometimes we will eventually decide to present speculative content first, because it has higher scientific impact.

Another way that we demonstrate our "hard-nosedness" to our readers is by making sure that Part 2 does not overshadow Part 2 in terms of length. If 90% of our Discussion is focussed on the more speculative Part 2, we may lose credibility. I suggest you should aim for at least 60%/40% (Part1/Part2) split: in expanding Part 1 you will often find that you start to include background information that is much appreciated by your readers.

Minor parts of the Discussion

Two optional, but highly recommended, minor parts of the Discussion are

- An introductory paragraph that reiterates the SRQ/s and Research Objectives, and then provides a very abbreviated overview of the Discussion as a whole (i.e. a Frame of Reference). This provides a useful navigational guide to what may be the longest section of the paper. Ideally, this paragraph's landmark sentence should also serve as a landmark sentence for the entire Discussion.

- A concluding paragraph that very succinctly recapitulates the main findings and their implications.

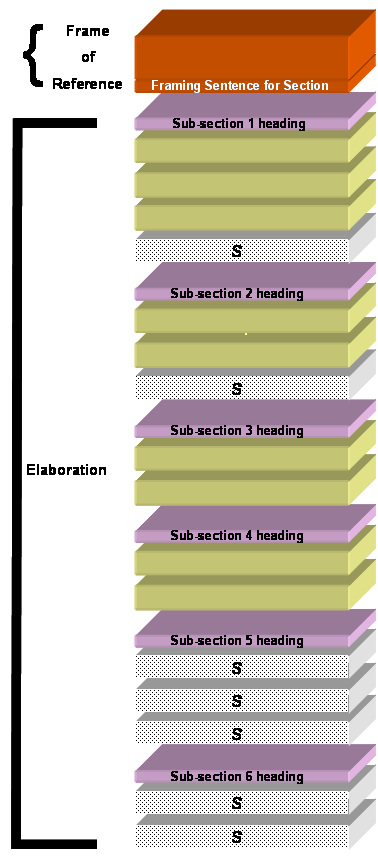

The diagram below depicts a seven-paragraph long Discussion in which any speculative content is indicated by speckling and the letter "S". It has an introductory paragraph, and a two-part elaboration. ( Note: "Framing Sentence" should read "Landmark Sentence"). There is no concluding paragraph.

Part 1 consists of paragraphs 2-5, and note that while paragraphs 2 and 3 conclude with speculative content, but there are no entirely speculative paragraphs.

Part 2 is shorter, consisting of paragraphs 6 and 7, and is focussed entirely on speculative content.

In a descriptive paper, Part 1 is still required

Authors often think that the "payload" of a descriptive paper is delivered in the Results. For example in a paper whose SRQ is:

- Which species of frogs are found in Kanha National Parks?

they might think that the answer to this question is provided, for example, by a Table in the Results section showing the species of frogs found by the authors. But such a Table is actually supplying the answer to a Research Objective level question, perhaps:

- Which species of frogs are detected by listening for evening calls along three transect lines of one kilometre length extending over an altudinal gradient of 300m-1500m?

Thus in Part 1 of the Discussion of such a descriptive study you might address questions such as:

* How does the information obtained by the sampling procedure shape up against the what would have been obtained using a more exhaustive sampling approach, in terms of the information's

- completeness?

- reliability?

* In what ways was the information obtained

- expected?

- unexpected?

The second question in particular will involve comparison with any papers that supply related information.

As to the sequencing of non-speculative and speculative content, you should follow that suggested already. For example, only after having detailed the ways in which the obtained information matches or does not match expectations, should you progress to speculation about why.

......