The Science Of Scientific Writing Set G The Introduction The Pivot Point of the Paper Challenges to Coherence Exercise 1 Hand in Glove Exercise 2 Final Page .

OVERVIEW: The way to well-written science

PART I: Paragraphs and Sentences

SET A: Paragraphs: The Maps Behind Them

SET B: Paragraphs: Using Maps to Meet Readers' Expectations

SET C: Paragraph Coherence and Cohesion

SET D: Sentences

SET E: Scientific Sections (including Methods)

SET F: Scientific Sections: The Discussion

SET G : Scientific Sections: The Introduction

SET H : The Paper as a Whole

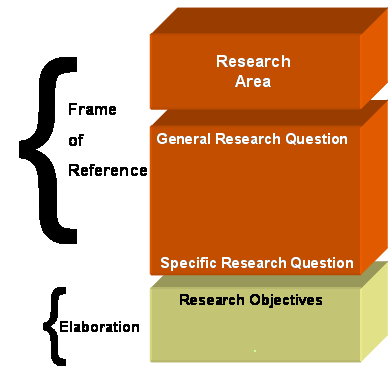

The Specific Research Question is the pivotal point of the Introduction - and the Paper's contract statement

When we consider the Introduction as a Section, then the sentence that expresses the Specific Research Question (SRQ) is the pointer Sentence for the Section. Thus it is already of great importance. But it is even more important than this, because at the level of the paper as a whole it is also the paper's Pointer Sentence. It is thus critical to handle it properly. One story that George Gopen tells in this book is of a senior academic who first became consciously aware of the importance of having a Poiner Sentence after having had a paper rejected for the first time in twenty years. The academic realised his Introduction did not have one, and after adding one and submitted the paper again, with no other chamges, and this time to a higher impact journal. It was quickly accepted, and the author lavished with praise for the brilliance of his work!

To give another view of the importance of the SRQ, George Gopen refers to the Ponter Sentence of the Introduction as the paper's "Contract Statement" : it is what you as the author promise to fulfill - by provding an answer to the stated problem.

Let's look at what is involved in best managing the SRQ

1. You must decide what the real SRQ is (or are, if there are several). This is easy: it is the question/s to which your title is the answer (or if the title is a also question, they are the same).

2. The SRQ should be a presented as a concluding "standalone" Point Sentence in the paragraph where it is located.

Readers expect to be led towards the Introduction's Pointer Sentence, they should be made to anticipate its arrival. The question should be located in a single sentence - not spread over several - and largely understandable in its own right (e.g. "Thus whether “indoor-time-associated” asthma involves indoor or outdoor allergens is an ongoing issue.")

3. One must prevent the reader confusing the real SRQ with other candidate SRQs. Remember that we often have three, four or more levels of questions in a typical Introduction. Unless you take measures to avoid it, readers can end up very frustrated if they find themselves repeatedly deciding that they have located the "point" of the paper, only to have their hopes dashed a sentence or two down the track. The three paragraph format I suggest here is largely designed to prevent such confusion. Let me explain:

* In paragraph 1, the emphasis should be on what is known, rather than what is unknown. This will naturally dissuade readers from imagining that any questions are being posed, even though they may be subtly implied. The other strategy is to keep the level of generality high: readers will assume that you are providing background material.

There are other subtle advantages in focusing on accepted knowledge in the first paragraph. It sets up a positive tone for the paper - it is rather dispiriting when authors say something like: "Despite three decades on work on this topic, we basically know nothing"! Also, when your paper is being reviewed, there is a good chance that the reviewers are some of the people who have spent significant parts of their lives trying to move the field forward. Better not to tell them it's been a waste.

* In paragraph 2, immediately switch the focus to what is not known (e.g. "The reasons for the increasing prevalence of asthma are unclear."). Within this paragraph you can pose as many questions as you like - the reader will safely interpret all but the last as mere stepping stones to the real SRQ at the end of the paragraph. But you must make sure to to leave out any mention of your current paper's attempts to address any of these questions. All potential questions are posed as having been the focus of previous work: "Recently Ghetarlyfe (2003) has suggested that it is decreased time spent outdoors that is possibly the causative factor.". As such, paragraph two has the impersonal tone of a (very brief) literature review, and it is a argument disguised as a description.

* In paragraph 3, your job is to make it clear that the SRQ has already been posed, and that any questions in this paragraph are Research Objectives. This is easy to do. You just change tone to personal reporting (although again, it is still really an argument) : "To address this question, we have followed up the group of 5,000 children originally surveyed by Ceeger and Neentendough (1988). Our approach, in which we cross-correlate the antibodies present in the children with antigens found in their indoor and outdoor environments, allows us to identify the likely source of the antigens that cause attacks experienced by these children." If you do not change tone when presenting your objectives in this paragraph, then the reader will (1) feel frustrated at having being led up a blind alley in paragraph 2 (2) try to interpret one of your objectives as the SRQ.

......