The Science Of Scientific Writing Set C Coherence &Cohesion Coherence I Exercise 1 Coherence II Exercise 2 Cohesion Exercise 3 Final Page.

OVERVIEW: The way to well-written science

PART I: Paragraphs and Sentences

SET A: Paragraphs: The Maps Behind Them

SET B: Paragraphs: Using Maps to Meet Readers' Expectations

SET C: Paragraph Coherence and Cohesion

SET D: Sentences

SET E: Scientific Sections (including Methods)

SET F: Scientific Sections: The Discussion

SET G : Scientific Sections: The Introduction

SET H : The Paper as a Whole

Local cohesion

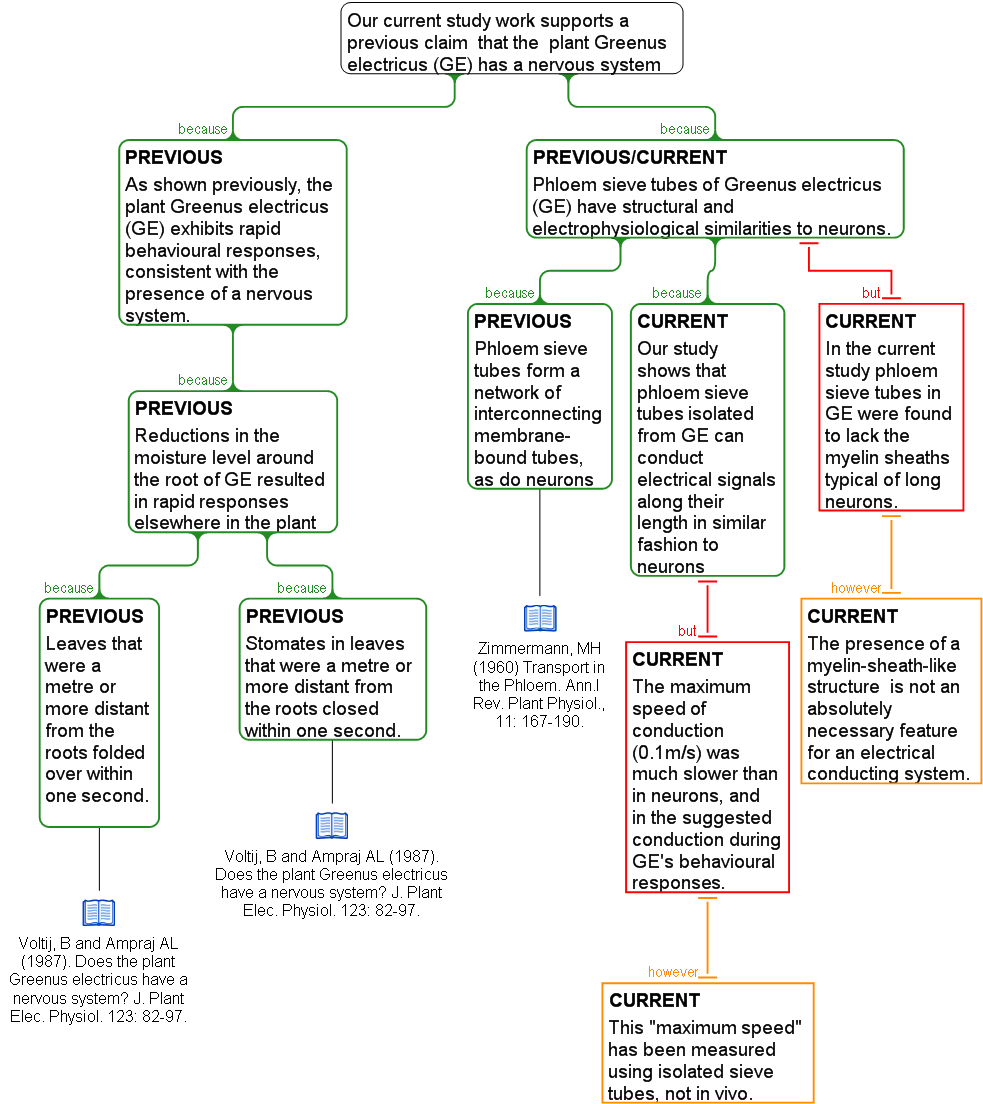

Read through the map below, which will form the basis of a single-paragraph text:

The argument presented here is relatively complex, with information ranging over work past and present, and drawn from a range of different scientific sub-disciplines. Interpreting the information is however greatly simplified by the fact that we can see how each individual statement relates to its neighbours. We can also see how certain statements are connected in clusters (i.e. branches). Of course, a written paragraph of course lacks such explicit diagrammatic navigational assistance, and to compensate for this writers need to add in extra "sign-posting" text. If they do not, as a reader moves from sentence to sentence, they will be unclear about the type of inter-relation any two successive sentences are meant to have. When there is a lot of sentence-to-sentence uncertainty the paragraph is said to lack cohesion.

Below are two versions of a paragraph based on this map. Which one do you think reads better?

Version 1: Our current study work provides some support for a previous claim that the plant Greenus electricus (GE) has a nervous system. GE exhibits rapid behavioural responses consistent with the presence of a nervous system (Voltij and Ampraj, 1987). The moisture level around the root having been experimentally reduced, leaves folded and stomates closed, these changes occuring over a metre or more from the roots and within one second (Voltij and Ampraj, 1987). The electrophysiological and structural features of the phloem sieve tubes of GE were studied by us, since this system forms a network of interconnecting membrane-bound tubes, just like neurons (Zimmerman,1960). Phloem sieve tubes isolated from GE can conduct electrical signals along their length in similar fashion to neurons. The maximum speed of conduction (0.1m/s) was much slower than both that of neurons and that suggested by GE's behavioural responses. Our measurements were made using isolated sieve tubes and in vivo speeds would probably be higher. W e found that sieve tubes lack the myelin sheath typical of long neurons. A myelin-sheath-like structure is not an absolutely necessary feature for an electrical conducting system.

Version 2: Our current study work provides some support for a previous claim that the plant Greenus electricus (GE) has a nervous system. Voltij and Ampraj (1987) showed that GE exhibits rapid behavioural responses consistent with the presence of a nervous system. For example, they found that when the moisture level around the root was experimentally reduced, leaves folded and stomates closed, these changes occuring over a metre or more from the roots and within one second. To further this work, we decided to investigate the electrophysiological and structural features of the phloem sieve tubes of GE, since this system forms a network of interconnecting membrane-bound tubes, just like neurons (Zimmerman,1960). We have shown that phloem sieve tubes isolated from GE can conduct electrical signals along their length in similar fashion to neurons. While the maximum speed of conduction (0.1m/s) was much slower than both that of neurons and that suggested by GE's behavioural responses, our measurements were made using isolated sieve tubes. In vivo speeds would probably be higher. In terms of structure, we found that sieve tubes lack the myelin sheath typical of long neurons, but of course a myelin-sheath-like structure is not an absolutely necessary feature for an electrical conducting system.

Most people will pick the second version, and they do so, firstly, because several of its sentences (as shown in bold below) begin with a brief phrase that tells us what is happening when we move from one sentence to the next. The phrases either:

a. Suggest the type of relationship between two adjacent sentences (e.g. claim/reason = for example; claim/objection =while). In terms of how the two sentences would fit on a map, it suggests that the second would lie directly under the first on the same branch.

b. Emphasise that in moving from one sentence to the next that we have also shifted from one major cluster of information to another - the equivalent of moving from one whole branch of the map to another (To further this work; In terms of structure)

Version 2: Our current study work provides some support for a previous claim that the plant Greenus electricus (GE) has a nervous system. Voltij and Ampraj (1987) showed that GE exhibits rapid behavioural responses consistent with the presence of a nervous system. For example, they found that when the moisture level around the root was experimentally reduced, leaves folded and stomates closed, these changes occuring over a metre or more from the roots and within one second. To further this work, we decided to investigate the electrophysiological and structural features of the phloem sieve tubes of GE, since this system forms a network of interconnecting membrane-bound tubes, just like neurons (Zimmerman,1960). We have shown that phloem sieve tubes isolated from GE can conduct electrical signals along their length in similar fashion to neurons. While the maximum speed of conduction (0.1m/s) was much slower than both that of neurons and that suggested by GE's behavioural responses, our measurements were made using isolated sieve tubes. In vivo speeds would probably be higher. In terms of structure, we found that sieve tubes lack the myelin sheath typical of long neurons, but of course a myelin-sheath-like structure is not an absolutely necessary feature for an electrical conducting system.

The other reason why the second version reads better is that near the start of many sentences we find information that clarifies whether the information that is to follow is previous or current, one of the other main navigational difficulties that needs to be dealt with in this paragraph (in the map it is handled by the very obvious annotations).

Version 2: Our current study work provides some support for a previous claim that the plant Greenus electricus (GE) has a nervous system. Voltij and Ampraj (1987) showed that GE exhibits rapid behavioural responses consistent with the presence of a nervous system. For example, they found that when the moisture level around the root was experimentally reduced, leaves folded and stomates closed, these changes occuring over a metre or more from the roots and within one second. To further this work, we decided to investigate the electrophysiological and structural features of the phloem sieve tubes of GE, since this system forms a network of interconnecting membrane-bound tubes, just like neurons (Zimmerman,1960). We have shown that phloem sieve tubes isolated from GE can conduct electrical signals along their length in similar fashion to neurons. While the maximum speed of conduction (0.1m/s) was much slower than both that of neurons and that suggested by GE's behavioural responses, our measurements were made using isolated sieve tubes. In vivo speeds would probably be higher. In terms of structure, we found that sieve tubes lack the myelin sheath typical of long neurons, but of course a myelin-sheath-like structure is not an absolutely necessary feature for an electrical conducting system.

Notice that in all cases, navigational information works best if it located near the beginning of a sentence. This is because it is basically providing a "frame of reference" which always works better earlier rather than later.

......