The Science Of Scientific Writing Set C Paragraphs with something extra: points and tails Paragraphs that end with a bang! Using maps to write Point-final paragraphs Exercise 1 Exercise 2 Exercise 3 Further ideas on Point-final paragraphs Exercise 4 Paragraphs that are short, or have a tail Final Page.

OVERVIEW: The way to well-written science

PART I: Paragraphs and Sentences

SET A: Paragraphs: The Maps Behind Them

SET B: Paragraphs: Using Maps to Meet Readers' Expectations

SET C: Paragraphs with Something Extra: Points and Tails

SET D: The Generic Section: Expectations and Maps as Blueprints

SET E: Scientific Sections: The Methods and Results

SET F: Scientific Sections: The Discussion

SET G : Scientific Sections: The Introduction

SET H : Sentences

SET I : The Paper as a Whole

PART II: The Paper and its Sections

SET 1: Argument Parts

SET 2: Indicator Words

SET 4: Locating Arguments in Prose

SET 5: Rationale's Essay Planner

SET 6: Evidence in Arguments: Basis Boxes

Synthesis 1: Position-Early Paragraphs

Synthesis 2: Position-Final Paragraphs

Synthesis 3: Writing a Discussion I

Synthesis 4: Writing a Discussion II

Further ideas about Point-Final Paragraphs

Why isn't the Point-final pattern used more often?

Given the importance of argument in scientific writing, and the fact that the Point-final pattern helps the writer to appear a less arrogant arguer, you might wonder why this pattern is not used more often. Two possible causes of its infrequent use in a research paper are that it is less direct, and a little 'artificial'. A Framing Sentence expressed as a question is a little less direct than when expressed in declarative mode. Also, a reader confronted with repeated use of such questions will probably find it a somewhat tiresome device. This will especially be the case if the writer continually uses explicit rather than implicit questions.

Can one write a paragraph where there is more 'reversal'?

In the Point-final pattern described in this set, the flow pattern of the main body of the paragraph is unaffected. Why don't writers reverse more of the paragraph flow, for example, by reversing the sequence in a component part of a paragraph (e.g. the equivalent of a branch in a map)?

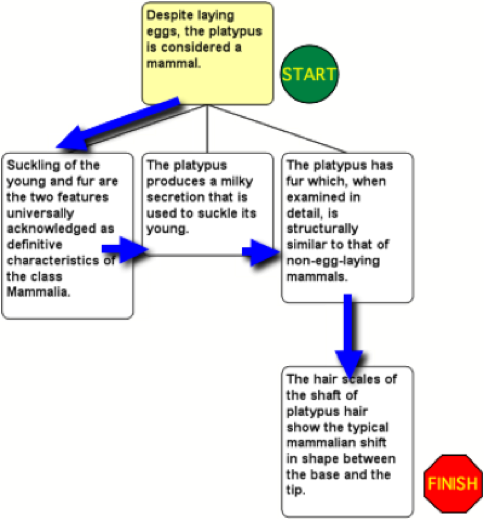

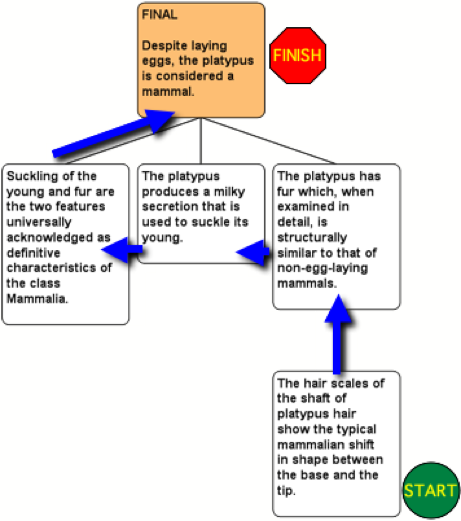

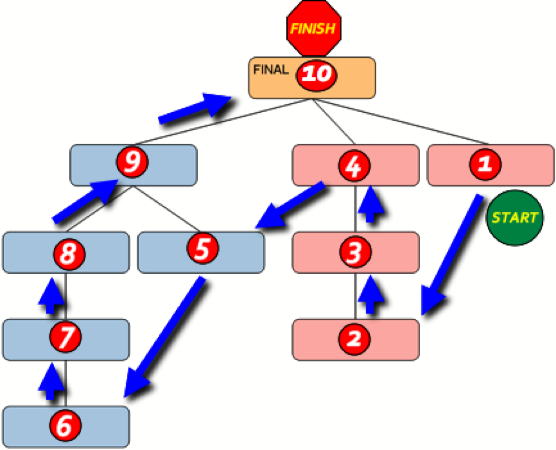

To understand why this rarely happens, consider the diagrams below:

In a situation of complete reversal (right) there is no Framing Sentence and as we proceed though the map we always go up branches. This 'upstream' pattern is more obvious in an extended diagram:

Working up branches will typically generate a more difficult paragraph, because the bottom boxes generally contain information of a more specific, less familiar nature (e.g., in the platypus example: 'The hair scales of the shaft show the typical mammalian shift in shape between the base and the tip.' ). Therefore working up a branch will often generate a paragraph that ignores one of the reader's strongest expectations: that familiar information will be provided before unfamiliar. This "Familiar First" approach is a central recommendation of Reader Expectation Theory, and it is really not a new idea for you: in this course I have already emphasised the need for providing an early frame of reference, and this typically equates to providing familiar material to the reader.

To demonstrate the difficulties of a paragraph written in completely reversed sequence, this is the text generated by the right-hand diagram further up the page:

The hair scales of the shaft of platypus hair show the typical mammalian shift in shape between the base and the tip. Therefore the platypus has fur which, when examined in detail, is structurally similar to that of non-egg-laying mammals. The platypus also produces a milky secretion that is used to suckle its young. These two features are universally acknowledged as definitive characteristics of the class Mammalia. Therefore, despite laying eggs, the platypus is considered a mammal.

This is not to say that one should never reverse the sequence within one or more 'branches' of a paragraph. This can be done, particularly in a Conclusion to the Discussion, perhaps the one place in a paper where readers do expect some literary flair. A writer could aim for greater dramatic effect by reversing more of the paragraph flow than has been recommended here. But this will require more skill on the writer's part to overcome the inherent communicative difficulties of 'reverse' writing. The same advice also applies to writing a Point-Final paragraph without a Framing Sentence - it can be done, but the writer needs to employ sophisticated techniques (not considered here) to compensate for the absence.

......