The Science Of Scientific Writing Set C Paragraphs with something extra: points and tails Paragraphs that end with a bang! Using maps to write Point-final paragraphs Exercise 1 Exercise 2 Exercise 3 Further ideas on Point-final paragraphs Exercise 4 Paragraphs that are short, or have a tail Final Page.

OVERVIEW: The way to well-written science

PART I: Paragraphs and Sentences

SET A: Paragraphs: The Maps Behind Them

SET B: Paragraphs: Using Maps to Meet Readers' Expectations

SET C: Paragraphs with Something Extra: Points and Tails

SET D: The Generic Section: Expectations and Maps as Blueprints

SET E: Scientific Sections: The Methods and Results

SET F: Scientific Sections: The Discussion

SET G : Scientific Sections: The Introduction

SET H : Sentences

SET I : The Paper as a Whole

PART II: The Paper and its Sections

SET 1: Argument Parts

SET 2: Indicator Words

SET 4: Locating Arguments in Prose

SET 5: Rationale's Essay Planner

SET 6: Evidence in Arguments: Basis Boxes

Synthesis 1: Position-Early Paragraphs

Synthesis 2: Position-Final Paragraphs

Synthesis 3: Writing a Discussion I

Synthesis 4: Writing a Discussion II

Paragraphs that end with a bang!

Consider the following paragraph, with particular attention to the sentences in bold. (Background: Cells in the body often need to commit suicide, and when they do, an enzyme called Ran stops doing its normal job within the nucleus, and becomes dispersed throughout the cell. This redistribution of Ran can be seen when mammalian cells are treated with the cellular poison VP16 (a chemotherapy drug). The researchers involved in this study investigated whether the normal localization of Ran within the nucleus requires the presence of another protein, called RCC1. They removed normal RCC1 from the cells by exploiting a special type of mutant cell (tsBN2). The gene that makes RCC1 in these cells generates a normal version of RCC1 at low temperature, but an unstable version at high temperature.)

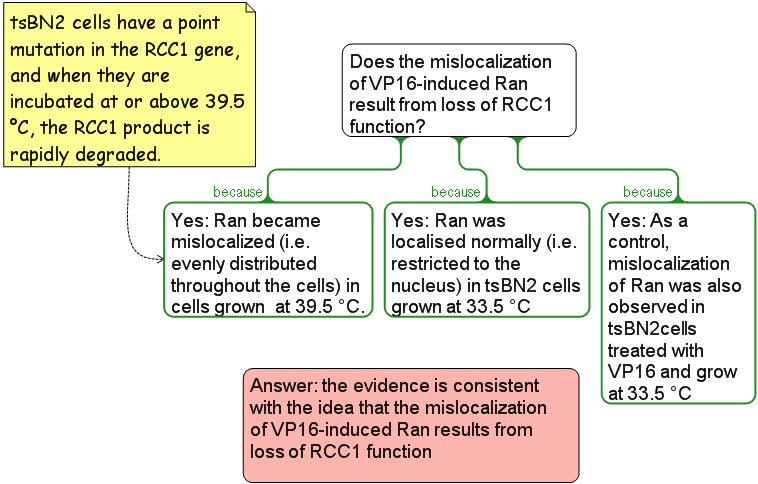

To test the possibility that mislocalization of VP16-induced Ran could result from loss of RCC1 function, temperature-shift experiments were performed using tsBN2 cells. tsBN2 cells have a point mutation in the RCC1 gene, and when they are incubated at or above 39.5 °C, the RCC1 product is rapidly degraded. tsBN2 cells were first grown at either 33.5 °C or 39.5 °C for 6 h, and were then immunostained for Ran. We found that Ran was localised normally in cells grown at 33.5 °C but became evenly distributed throughout the cells at 39.5 °C. In a further experiment, in which tsBN2 cells were grown at 33.5 °C only, mislocalization of Ran could also be brought about by treatment with VP16. Our observations suggest that mislocalization of Ran induced by VP16 could be due to loss of RCC1 function.

The first four sentences conform to the pattern we looked at in Set B. Sentence 1 is a Framing Sentence, and Sentences 2 through 4 are an obvious Elaboration. But the final sentence has a different type of relationship to Sentence 1: instead of elaborating, it draws upon the preceding elaboration to provide an answer to the question implied by the first sentence (The explicit question is: "In tsBN2 cells, is the mislocalization of VP16-induced Ran due to loss of RCC1 function?"). This concluding content is clearly the single most important piece of information in the paragraph, and if a paragraph has such singular content, it is called its point. The conclusion of a paragraph is one of only two locations where a point should be positioned, the other being the Framing Sentence itself.

If we were to map a point-final paragraph, the example below shows the format to use. Use a Claim box for the Point Sentence, colour it red, and place it under the main map, unconnected.

Roles of the Point-final Paragraph

Paragraphs with a final point are mostly used in a few special situations in a research paper: in the Introduction (very common) and for the first and last paragraphs of the Discussion (optional). They are sometimes used in Arguments in the Discussion and occasionally they will be used in the Results (in the case above, the authors have slipped out of pure Report mode, into Argument mode).

The Point-final pattern can play different roles in arguments in a scientific paper:

- In the Introduction especially, it allows you to familiarise your readers with difficult concepts and obscure terminology, so that when you do finally come to express the point, it can be done in a single, succinct sentence. This can help deliver a more memorable "take home message".

- Again, in the Introduction especially, it can "free up" the Framing Sentence location, which can now be used to provide information of more general interest.

- In an argument anywhere in the paper, putting the conclusion last can help to make you, as the writer, appear less arrogant. You are more likely to come across as the sort of person who gives readers the evidence first, and lets them make up their own minds, rather than telling them what to think.

- In an argument in the Conclusion of the Discussion, the effect of a concluding point can be dramatic.

A (long) Point-final Paragraph must still have a Framing Sentence

Many writers are naturally inclined towards the Point-final format (probably because, verbally, we often argue in this way) but when employing it, they often make the mistake of omitting a Framing Sentence. In speech, the equivalent of a Framing Sentence is often rendered unnecessary by context or verbal cues (e.g. intonation), but in a text, context can often be lacking (readers cannot be assumed to read linearly) and there is no recourse to verbal cues. It is therefore vitally important to provide a Framing Sentence for all types of long paragraphs.

The various types of Framing Sentence

To create a Framing Sentence for a Point-final paragraph you will often need to work backwards, because writers typically start by only knowing what the Point is meant to be. In working backwards (we will see how to do this on the next page) it first helps to know the various types of relationship that can exist beween Framing and Point Sentences. We have already seen one of the most commonly found types in scientific text: Question and Answer. The question may be posed explicitly (i.e. the sentence ends with a question mark) or implicitly (i.e. the question is suggested). The difference betwen an explicit and implicit question can be appreciated by considering the two sentences below:

(1) Does the mislocalization of VP16-induced Ran result from loss of RCC1 function?

(2) To test the possibility that mislocalization of VP16-induced Ran could result from loss of RCC1 function, temperature-shift experiments were performed using tsBN2 cells.

Sometimes the implication of a question is extremely subtle. Compare the Framing and Point Sentences of a single paragraph below:

Framing Sentence: Each of our results is consistent with an involvement of zinc poisoning in the epidemiology of Blatter's Disease.

Point Sentence: Considered together, the results provide strong support for the idea that Blatter's Disease is the result of zinc poisoning

The subtle implication in the Framing Sentence is that a single result is inherently weak when used to explain a causal link between two phenomena. An explanation is always considered stronger if supported by multiple lines of evidence. To some extent, any claim that is put foward as a Framing Sentence has a tentative quality about it, otherwise you would not feel the need to provide evidence to back it up! Thus we often find that at the end of the paragraph writers simply repeat the Framing Sentence as a Point Sentence, as if they are saying, "Well now you can actually believe what I said at the start"!

Another very important type of relationship between Framing and Point Sentences is: Question and Further Question. Consider the following paragraph, with emphasis on the Framing and Point Sentences (in bold):

Eighteenth-century biologists were confounded by the platypus. Egg-laying, one of the platypus's most striking features, was a characteristic not normally associated with a mammal, but its hairy covering was. So they had to look more closely to answer the question: is the platypus a mammal? They found that the platypus's fur, when examined in detail, is structurally similar to that of accepted mammals. The hair scales of the shaft of platypus hair show the typical mammalian shift in shape between the base and the tip. Also, although it has no teats, the platypus nevertheless produces a milky secretion that is used to suckle its young. Suckling of the young and fur were two features universally acknowledged at the time as definitive characteristics of the class Mammalia. Therefore, the biologists now had to ask themselves: should egg-laying in itself exclude an animal from being classified as a mammal?

This pattern is very common in the Introduction where the most typical type of "Further Question" is a more specific question. Thus the exact type of relationship is: General Question and Specific Question. We saw this pattern in an example in the previous Set:

The reasons for the increasing prevalence of asthma are unclear. Ceeger and Neentendough (1988) have demonstrated that time spent indoors correlates strongly with the incidence of childhood asthma. Durstmeight (1990) later provided some evidence that prolonged exposure to household allergens could be important, but it has not yet been shown definitively that indoor allergens are responsible. Recently, Ghetarlyfe (2003) has suggested that it is decreased time spent outdoors that is possibly the causative factor. In this as yet untested scenario it would be outdoor, not indoor, allergens that are responsible: children might be getting fewer opportunities to develop an insensitivity to agents such as pollen and fungal spores that occasionally reach high densities, since they not being exposed to them at low levels. Thus whether indoor-time-associated asthma of children involves indoor or outdoor allergens remains an ongoing issue.

......