The Science Of Scientific Writing Set H Location in Sentences Multi-part Sentences Exercise 1 Maps for Sentences Exercise 2 Simple Sentences Final Page .

OVERVIEW: The way to well-written science

PART I: Paragraphs and Sentences

SET A: Paragraphs: The Maps Behind Them

SET B: Paragraphs: Using Maps to Meet Readers' Expectations

SET C: Paragraphs with Something Extra: Points and Tails

SET D: The Generic Section: Expectations and Maps as Blueprints

SET E: Scientific Sections: The Methods and Results

SET F: Scientific Sections: The Discussion

SET G : Scientific Sections: The Introduction

SET H : Sentences

SET I : The Paper as a Whole

PART II: The Paper and its Sections

SET 1: Argument Parts

SET 2: Indicator Words

SET 4: Locating Arguments in Prose

SET 5: Rationale's Essay Planner

SET 6: Evidence in Arguments: Basis Boxes

Synthesis 1: Position-Early Paragraphs

Synthesis 2: Position-Final Paragraphs

Synthesis 3: Writing a Discussion I

Synthesis 4: Writing a Discussion II

Maps as guides to multi-part sentence construction

On the previous page, we saw how you might shuffle around the parts of a multi-part sentence to achieve a desired effect. In doing so, you had to make decisions about what was the most important part of the sentence. Interestingly, if you use a mapping approach to plan your text, e.g. a paragraph, then you will already have done much of the thinking that helps determine the best sequence of sentences and sentence parts. Let us consider an example, which will tell us a lot about the origin of sentence parts, and how to use multi-part sentences to their greatest advantage.

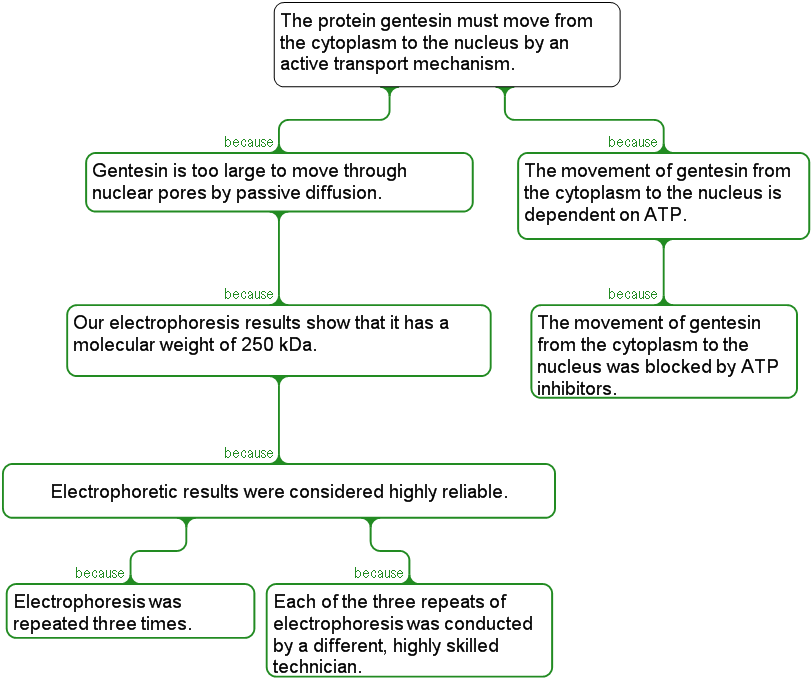

Read through the paragraph map below:

As argument maps go, this one is fine: each box contains a simple statement, indicating that the argument has been broken down into its constituent parts. When we read the map, it makes perfect sense. But if we write it up as follows, creating one sentence from each box, and removing repeated material, the text is jerky and stilted:

The protein gentesin must move from the cytoplasm to the nucleus by an active transport mechanism. It is too large to move through nuclear pores by passive diffusion. Our electrophoresis results show that it has a molecular weight of 250 kDa. These results were considered highly reliable. The electrophoresis was repeated three times. Each of the three repeats was conducted by a different, highly skilled technician. The movement of gentesin from the cytoplasm to the nucleus is dependent on ATP. This movement was blocked by ATP inhibitors.

Also, it is not as readily comprehensible as the map, where for example, we can see immediately that there are two lines of argument. one large, one small. We can also readily see, in the map, that all the evidence is supportive, which need not always be the case of course. Some of these problems can be addressed by adding in navigational text:

There are two lines of evidence that indicate that the protein gentesin must move from the cytoplasm to the nucleus by an active transport mechanism. First, it is too large to move through nuclear pores by passive diffusion. Our electrophoresis data show that it has a molecular weight of 250 kDa. This result was considered highly reliable. The electrophoresis was repeated three times. Each of the three repeats was conducted by a different, highly skilled technician. Second, the movement of gentesin from the cytoplasm to the nucleus is dependent on ATP. This movement was blocked by ATP inhibitors.

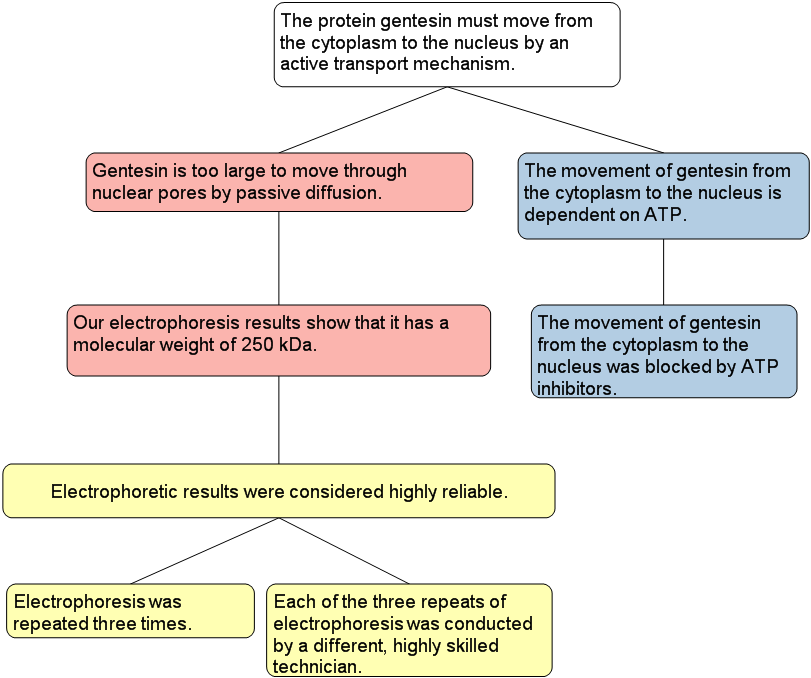

But there is still room for improvement, because we can combine some of the individual sentences that "belong" together. To my mind, the colour scheme below depicts a sensible grouping, and leads to the text below the map.

There are two lines of evidence that indicate that the protein gentesin must move from the cytoplasm to the nucleus by an active transport mechanism. First, it is too large to move through nuclear pores by passive diffusion, since electrophoresis shows it has a molecular weight of 250 kDa. This result was considered highly reliable, because the electrophoresis was repeated three times, and each repeat was conducted by a different, highly skilled technician. Second, the movement of gentesin from the cytoplasm to the nucleus is dependent on ATP, as shown by the blocking of this movement by ATP inhibitors.

Notice how in each of the three multi-part sentences, the sequence of the parts is exactly the same as for the component sentences in the map. Therefore, if you have a created a map that reads well as a map, and you can see a sensible grouping system for the sentences, then there is little more to do. The sequence of parts in a multi-part sentence merely reflects the logical relationship of the group of "original" simple sentences from which it is derived.

Note: In linguistics, it is a well accepted that the parts of a multi-part sentence are best thought of as individual sentences that have been welded together, often after considerable compression of some of the parts (e.g. see Doing Grammar, by Max Morenberg).

......