The Science Of Scientific Writing Set D Introduction Multi-part Sentences The End of the Sentence Exercise 1 The Start of the Sentence The Middle of the Sentence Sentence, Paragraph compared Mapping Multi-part Sentences Exercise 2 Types of Sentence Part Exercise X Advanced Sentence Stories Final Page .

OVERVIEW: The way to well-written science

PART I: Paragraphs and Sentences

SET A: Paragraphs: The Maps Behind Them

SET B: Paragraphs: Using Maps to Meet Readers' Expectations

SET C: Paragraph Coherence and Cohesion

SET D: Sentences

SET E: Scientific Sections (including Methods)

SET F: Scientific Sections: The Discussion

SET G : Scientific Sections: The Introduction

SET H : The Paper as a Whole

Sentence Strategy #1: as with paragraphs, you can exploit the reader's expectation of where different types of information will be located

Part II: The Start of the Sentence

Let us consider a sentence with three parts:

A most important factor in animal speciation is geographical isolation, a powerful generator of genetic variation, and a phenomenon that explains many divergences in the evolution of snakes.

The landmark of this sentence, the final part, remains the same as the two-part version we looked at earlier. But what are the roles of the initial and middle parts?

The first part/s of a sentence provide Frame-of-Reference information, that helps us to interpret the rest of the sentence

In the example above the information, "A most important factor in animal speciation is geographical isolation" establishes a Frame of Reference for the remainder of the sentence, by alerting us to the part played by geographical isolation in animal speciation. As was pointed out previously when discussing the internal organisation of paragraphs, any text compartment (sentence, paragraph, section etc.) will always be clearer if it starts with information that orients the reader.

Frame-of-reference information can be of three types: content-related, navigational, and "character-establishing"

In the example above the sentence part "A most important factor in animal speciation is geographical isolation", clearly introduces information that specifically introduces us to the content that follows. Sometimes frame-of-reference information of the content-related type may be spread over more than one sentence part. For example consider the sentence below:

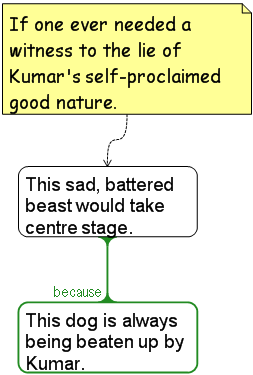

This dog is always being beaten up by Kumar, and if one ever needed a witness to the lie of Kumar's self-proclaimed good nature, this sad, battered beast would take centre stage.

If we map the logical relationship between its likely "source" sentences

then the second part of the original sentence appears to be providing a context for the claim "This sad, battered beast would take centre stage". Even if you do not agree with this map in its entirety there still seems a strong case that "if one ever needed a witness to the lie of Kumar's self-proclaimed good nature" is providing information of a frame-of-reference kind.

Content-related information is only one of three types of Frame-of-Reference information that can help orient the reader. The second type is navigational. For example consider this sentence:

The second most important factor in animal speciation is geographical isolation, a powerful generator of genetic variation, and a phenomenon that explains many divergences during bird evolution.

If we assume that this sentence is part of a larger text, then the word "second" tells the reader that the factor to be discussed in this sentence is one of at least two factors considered in the text as a whole. We have previously discussed navigational cues (when we discussed Local Cohesion in Set C) and we saw there that navigational cues inform the reader about several aspects of a text. For example, if we think about a map that might be the foundation for a text, then the text version may provide cues that tell us where we are in the source map, what sort of inter-relationship exists between two or more map components (e.g. claim/reason), and perhaps (for an argument or explanation) the overall importance of a given line of reasoning.

Here are two more sentences where the first sentence part provides a navigational cue:

As explained above, a most important factor in animal speciation is geographical isolation, and while it falls down in explaining bird evolution, it has been very generally successful in understanding divergences in other animal types.

As will be described in detail below, the hair samples were collected each day.

The third type of Frame-of-Reference information, character-establishing, is a little more subtle. To explain it, let's start by revisiting Kumar and his dog:

(a) Kumar proclaims himself to be a a nice guy, but he beats his dog.

(b) This dog is always being beaten up by Kumar, and if one ever needed a witness to the lie of Kumar's self-proclaimed good nature, this sad, battered beast would take centre stage.

The two sentences at first sight seem to tell much the same story, but where they differ is in whose story is being told. In version (a) most people would pick Kumar as the main character of the story, whereas in (b) the spotlight would seem to shift to the dog. Why? Well, let's get a little bit grammatical for a minute and look at the subjects of all the verbs in these sentences:

(a) Kumar proclaims himself to be a nice guy, but he beats his dog.

(b) This dog is always being beaten up by Kumar, and if one ever needed a witness to the lie of Kumar's self-proclaimed good nature, this sad, battered beast would take centre stage.

As suggested by these examples, the reader's interpretation of who is the sentence's main character depends mostly on who (or what) are the subjects of the verbs. In each of the sentence parts of (a) it is Kumar who is the verb's subject, and in (b) it is the dog that claims two of the three sentence parts. Later in the set we will consider how readers interpret an ambiguously mixed-subject sentence like the one below (subjects in bold).

Even though his dog shows signs of being beaten, Kumar insists he is a nice guy.

For the moment however the main thing to remember is that if the first part of a sentence has a verb, then the reader will automatically start by assuming that the main character of the sentence as a whole will be that verb's grammatical subject.

......